Key Takeaways

- Common autistic traits such as sensory processing differences, a need for predictability and routine, and interoception can affect eating habits.

- Research shows a high co-occurrence of autism and eating disorders, with autistic women in particular having a higher risk of developing EDs like anorexia nervosa and bulimia.

- Avoidant-Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) is closely aligned with autism because both conditions share overlapping traits, like sensory sensitivities.

- Autism-informed care is essential, as neurotypical approaches to eating disorder treatment are often ineffective for autistic patients. Autism-informed care involves providing sensory accommodations and offering flexibility around food exposure.

When my daughter was diagnosed with autism and ADHD a couple of years ago, suddenly, her lifelong eating challenges started to make sense: Her constant refusal to try new foods and her insistence on a “safe foods”-only diet was due to her neurodivergent brain.

While this is something we’re working on every day, and her nutrient intake is improving, I know she will still have to manage these eating differences in adulthood.

Autism can undoubtedly affect one’s eating habits or behaviors, and autistic people are at a higher risk of developing eating disorders. However, even though there are some overlaps, it’s important to recognize that eating differences in autistic adults aren’t necessarily a gateway to an eating disorder.

In this article, we’ll explain not only the overlap between autism and eating disorders but also clarify the deviations. Plus, we’ll discuss how to identify eating differences, as well as outline autism-informed eating disorder care.

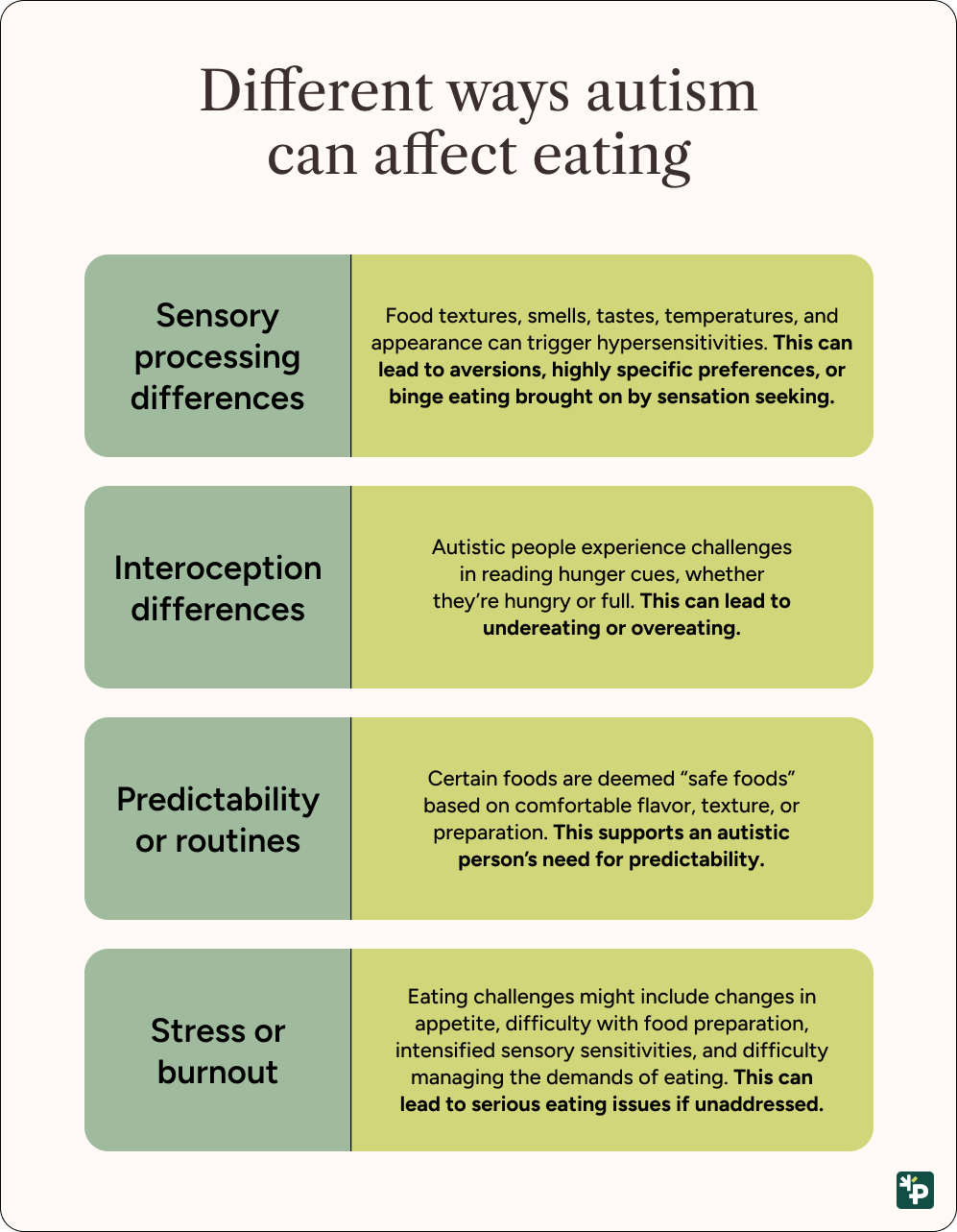

How autism can affect eating

As the parent of an autistic daughter, I know firsthand that there is a unique relationship between autism and food. What may appear to be picky eating can actually be common autistic traits like sensory processing differences or low interoception (the understanding of your body’s internal senses, such as hunger).

“Autistic traits, like differences in sensory processing, a need for predictability and routine, and interoceptive differences, in addition to the impact of stress and burnout, can cause eating challenges,” confirms Dr. Kelly Whaling, Research Lead and Licensed Clinical Psychologist at Prosper Health.

Below, Dr. Whaling breaks down how certain autistic traits can affect eating:

Sensory processing differences

For many autistic people, all the varying characteristics and sensory complexity of food can make the difference between a finished meal and an untouched one.

Dr. Whaling explains, “Food-specific sensory sensitivities are common among autistic people and typically emerge in early childhood, often predating any eating disorder development.” These sensitivities can range from aversive responses to food textures, tastes, smells, temperatures, or even the mixing of different foods. The result is a significant limitation on the types of foods a person can eat.

In addition to certain sensory sensitivities to individual foods, Dr. Whaling notes that busy restaurants or school cafeterias—both characterized by high noise levels, bright lighting, background music, strong smells, and multiple simultaneous conversations—can aggravate autism food aversion. These environments “can trigger a stress response in autistic individuals that suppresses appetite and makes eating difficult,” she says.

Predictability and routine

Since some autistic people have a strong need for predictability and routine, their eating habits often fall into this category. This can present in multiple ways, such as eating the same foods every day, needing meals at specific times, or only in certain environments. This can also include having very particular ways food must be prepared, served, or eaten.

These eating routines “create predictability in a world that often feels chaotic and overwhelming,” says Dr. Whaling. She also says that a common practice among autistic people is to have “safe foods”: Specific foods or brands that are predictable, tolerable, and won't cause distress.

“Safe foods” can differ significantly from one individual to another. Still, some examples of “safe foods” include plain pasta with butter (one of my daughter’s favorites!) or without anything, plain rice, specific types of crackers, particular fruits that have consistent textures, a protein shake that's always the same, or foods with very uniform textures.

“Safe foods often have predictable sensory properties: they taste the same every time, have consistent texture, are the same temperature, and don't have unexpected variations,” says Dr. Whaling.

Interoception differences (hunger, fullness, nausea)

Interoception is the understanding of the body’s internal senses. Autistic people commonly experience low interoception, which can cause difficulty in reading hunger cues. This can result in either undereating or overeating.

“Many autistic people depend on external cues like the time of day or portion sizes to regulate eating, rather than internal sensations,” says Dr. Whaling, pointing out that colloquial terms like “listen to your body” or “eat when you're hungry” can be challenging advice for autistic people.

Interoception can also present itself in autistic people as a hypersensitivity to internal sensations associated with eating and digestion. This includes feelings of bloating, fullness, and the physical process of digesting food. For some autistic people, such sensations are “intensely distressing and can lead to nausea or vomiting, or to food restriction as a means of avoiding these uncomfortable experiences,” explains Dr. Whaling.

Stress, burnout, and appetite changes

Autistic burnout from stress can cause serious eating challenges because, as Dr. Whaling observes, “when you’re burned out, everything becomes harder, including feeding yourself.”

Burnout-related eating difficulties can present as changes in appetite, difficulty with food preparation (due to challenges with task initiation or completion), increased reliance on routine and predictability (which means a higher tendency to stick with safe foods), intensified sensory sensitivities, and a lesser capacity to manage the demands of eating.

If you’re someone who is living with unrecognized autism, you may experience even more severe stress levels that are ultimately affecting your eating habits. “Living with unrecognized autism creates a particular kind of chronic stress that has effects on mental health and eating,” explains Dr. Whaling.

Why autistic people are at higher risk for eating disorders

Research has demonstrated a high co-occurrence of autism and eating disorders (EDs) such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia, with autistic women and people assigned female at birth showing a higher risk of developing EDs. About 20 to 30% of people with EDs also have autism (or display autistic characteristics).

Why this is the case is the bigger question, as the research suggests certain autistic traits can ultimately lead to the development of eating disorders.

“Some autistic people develop anorexia or bulimia after encountering health information that gets interpreted in black-and-white or absolutes,” explains Dr. Whaling. She highlights examples like a health class lesson on obesity or a person casually mentioning that “sugar isn’t good for you”: For some autistic people, not eating something like sugar can become an unbreakable rule.

“The literal, concrete way many autistic people process information means general advice can sometimes become absolute truth, and once that rule is established, it's incredibly difficult to break,” she says.

Autistic people can also develop eating disorders because they become coping mechanisms for managing overwhelming emotions, sensory experiences, or social stress. “Some discover that restrictive eating numbs confusing emotional experiences or creates a sense of control and predictability in an otherwise chaotic world,” observes Dr. Whaling.

Above all, just as autism exists on a spectrum, so do eating challenges. “For some people, these challenges remain difficult, but don't meet the criteria for an eating disorder,” says Dr. Whaling. “For others, the same underlying traits and experiences develop into clinical eating disorders.”

Read on for a further examination of how certain characteristics can affect autism eating habits and potentially lead to EDs.

Emotional regulation and alexithymia

Alexithymia is a condition where a person has difficulty identifying and describing their emotions. As there is a high overlap between alexithymia and autism, this condition can make emotional regulation more challenging for autistic people. When that happens, disordered eating may become a way to cope with this level of emotional dysregulation.

Anxiety, rigidity, and control under stress

While predictability and routine can offer regulation and safety for autistic people, this type of approach to food can also have a negative effect. Many autistic people go on "food jags," which is a tendency to eat the same foods, prepared the same way, every day, and sometimes every meal.

This behavior can sometimes go from rigid to restrictive. "Rule‑based eating can feel reassuring in an unpredictable world," says Dr. Meghan Fraley, a licensed clinical psychologist with Prosper Health, "and over time that rigidity can become harmful."

Burnout from social pressure and masking

For autistic people, high levels of stress from constant masking or camouflaging can have a detrimental effect on their eating habits: “The effort required to monitor and adjust body language, facial expressions, tone of voice, and conversation patterns throughout the day is exhausting and can leave little energy for other tasks, including eating adequately,” says Dr. Whaling.

Late diagnosis and unmet support needs

Delayed autism diagnosis, paired with an overarching lack of support, can have a negative long-term effect, possibly manifesting in an eating disorder: "Autistic people often experience years of invalidation, pressure to mask, and unmet support needs," notes Dr. Fraley. "Differences in emotional regulation, alexithymia, anxiety, rigidity, and a drive for control under stress can make rule‑based eating feel stabilizing."

Autism and anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by an intense fear of gaining weight. While there are significant differences between autism and anorexia, there are also several clinical overlaps. This may cause anorexia to present differently in autistic adults, making it more difficult to spot.

"In autistic adults, anorexia may be less overtly appearance‑driven and more rooted in predictability, sensory aversion, interoceptive confusion, anxiety, and rigid rule systems," says Dr. Fraley. "As nutritional status improves and starvation effects lessen, underlying autistic traits often become more visible."

These autistic traits can ultimately complicate recovery: "Hunger and fullness cues that existed prior to the eating disorder may be dismissed as denial," continues Dr. Fraley. "Sensory overwhelm may be interpreted as resistance. Without recognizing these distinctions, it becomes harder to provide support that actually helps."

There’s a also major disconnect between autistic anorexia patients and the prescribed end goal of treatment, which, says registered dietitian Gretchen Wallace, RD, is usually an intuitive eating program. (Intuitive eating is an approach focusing on hunger and fullness cues.) This can be challenging for autistic individuals who have low interoception and struggle to notice hunger cues. “Without solid interoceptive awareness, intuitive eating may not be a realistic goal,” observes Wallace.

If you are an autistic person and have received an anorexia nervosa diagnosis, seeking autism-informed care is imperative. This is because anorexia treatment often involves intensive programs and possibly residential care. And if these programs aren't autism-informed, they could potentially increase the stress and burnout level of the autistic patient. Treatment spaces that aren’t adapted for an autistic patient’s sensory needs can lead to increased sensory overload, thus precipitating meltdowns.

Autism and ARFID

One eating disorder that is closely aligned with autism is called avoidant-restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID).

ARFID and autism tend to go hand in hand because there is significant overlap between the two conditions: It’s common for autistic people to experience food sensory sensitivities, as well as strong food preferences—all of which are traits regularly associated with ARFID. (About 1 in 10 autistic individuals meet the diagnostic criteria for ARFID.)

ARFID is classified as an eating disorder because people with the condition severely limit their food intake. But unlike other EDs, like anorexia nervosa, people with an ARFID diagnosis are not hyperfixated on losing weight or their body image.

Unlike neurotypical picky eating, where people are usually still hungry and want to eat, those with ARFID would rather not eat, period. "When selective eating causes social, nutritional, or medical impairment, it may meet criteria for ARFID," clarifies Dr. Fraley.

Autism and other types of eating disorders

Autistic people can present very specific types of traits if they have eating disorders like bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder.

Bulimia nervosa is an ED where the person eats a large quantity of food at once, then purges it either by vomiting or using laxatives. Binge-eating disorder causes the person to eat unusually large amounts of food without stopping—even when they are full.

Autism and binge eating, however, present in a rather particular manner: With EDs like bulimia and binge-eating disorder, autistic clients may exhibit more ritualized behaviors, such as planning their binges, having specific binge foods, or eating foods in a specific sequence. Or even using a binge as a way to cope after an overstimulating day.

It's also worth noting the strong link between autism and eating too much, especially when someone has co-occurring ADHD. Those with ADHD often have poor impulse control, which can make them more susceptible to binge eating.

Why eating disorders in autistic adults are often missed

Wallace notes that it’s not just the autistic community that suffers from misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis. “Eating disorders are notoriously underdiagnosed across all populations,” she says. Unfortunately, she continues, “We live in a society that glorifies restricted eating, normalizes dieting, and blows off disordered eating as a ‘health journey.’”

There are, however, several reasons why EDs are often missed or misdiagnosed in neurodivergent adults. We break down these reasons below:

Gender bias and late-autism diagnosis

Since EDs are historically seen as an issue for teenage girls, they are largely underdiagnosed in male and transgender populations. Also, because many women and AFAB people tend to receive late autism diagnoses, autism is often not caught in eating disorder treatment centers and is just labeled as “anxiety,” hence impairing effective treatment.

Masking and “high-functioning” assumptions

Eating disorders are often heavily masked because there is usually a large shame component. Hiding an eating disorder can be seen as another layer of masking, especially for adults considered to have low-support autistic needs or, to use a more outdated and problematic term, “high-functioning autism.”

"There may be significant struggles with eating that come up in therapy," says Dr. Fraley, "but they’re not always clearly identified as eating‑related, especially when weight loss isn’t dramatic or when someone [has low-support needs]."

ED treatments that worsen autistic distress

Autistic patients may be reluctant to seek ED care because many of the treatments include inpatient or residential care. This kind of controlled environment would disrupt their routine, [potentially] have sensory overloading environments, and be too unpredictable.

Weight-centric and compliance-based models that might not work for autistic adults

Because the current recovery model for ED patients is predominantly neurotypical, treatment models need to be adapted to reflect autistic patients’ experience: We assume that if someone is “recovered,” they should be comfortable eating out, eating a wide variety of foods, eating at different times of day, and be flexible with food, and still eat at least three meals a day.

However, some autistic people may never like a wide variety of foods or enjoy eating in restaurants. Similarly, certain autistic people will always need to eat on an exact schedule due to their preference for routine.

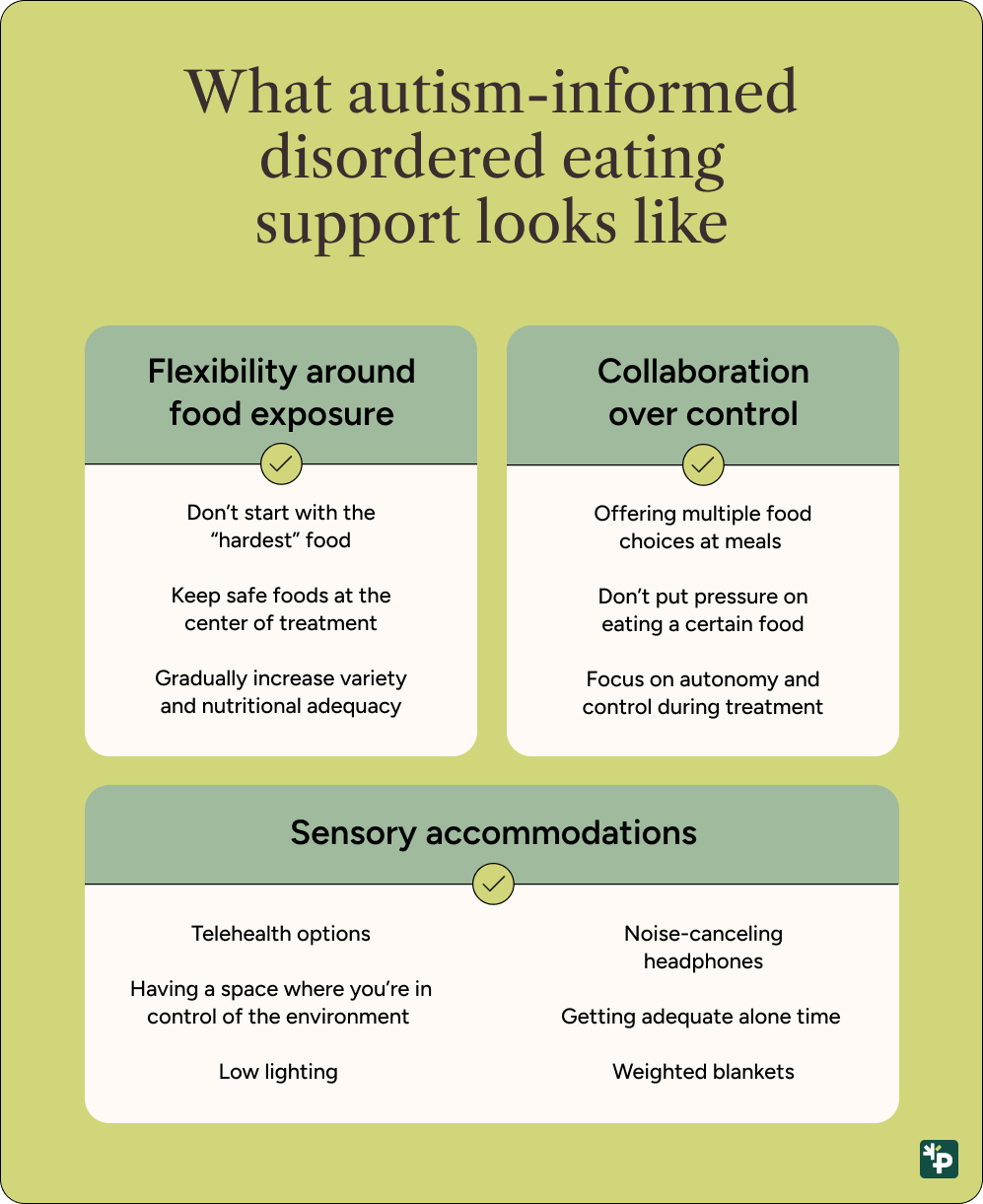

What autism-informed eating disorder care looks like

Autism-informed eating disorder care takes autistic traits into account when providing ED treatment. In treatment, the autistic individual and the clinician will work together to create an individualized treatment plan that acknowledges the patient’s autism, whether it’s their sensory issues, special interests, interoception, etc.

Sensory accommodations

There are several sensory accommodations that providers can offer their autistic clients:

- Telehealth options

- Low lighting in treatment spaces

- Avoiding overhead fluorescent lights in treatment spaces

- Providing noise-canceling headphones or earplugs during group activities or group therapy

- Using proprioceptive feedback during sessions like weighted blankets or weighted stuffed animals

- Allowing enough alone time in residential settings

- Having a space that is "yours" where your stuff isn't touched or moved in residential settings

Predictability and clear expectations

A set and predictable schedule and notifying people ahead of time of any changes can go a long way toward making autistic clients comfortable in treatment.

Flexibility around food exposure

Treatment often starts with safe foods, while still working toward increased variety and nutritional adequacy, explains Dr. Fraley: “The key is not starting with the hardest food.” For example, she says, if green beans are the “scariest” food, yet you’re just “slightly uncomfortable” with a different brand of bagel, you would likely start with the bagel. Having the bagel on the plate, taking one bite, and building gradually.

Collaboration over control

Studies have shown that current ED treatment is less effective for autistic individuals, which is all the more reason why autism-informed eating disorder care needs to be more widely implemented. “The eating disorder field has been heavily driven by anorexia-focused research and treatment models, and providers may not realize they’re viewing everything through that lens,” observes Dr. Fraley.

Even with accommodations, ED treatment progress may look slower from the provider’s perspective, but what’s more important is that this approach will be more sustainable for the autistic patient.

When to seek support — and what kind helps

If you feel that food is “stressing you out” and ultimately “making your life harder,” then it’s time to consider professional support, says Wallace.

Other signs to look for, according to Dr. Fraley, include medical concerns like rapid weight loss, dizziness, faintness, heart symptoms, and electrolyte issues. Psychological distress red flags as well: “If family meals involve meltdowns due to noise, smells, or pressure to eat, that’s a signal for support,” she says.

When seeking support, an autism-informed provider is essential. Dr. Fraley advises finding a clinician who doesn’t dismiss the eating disorder as “just autism,” and who understands ARFID subtypes (lack of interest, sensory overwhelm, preference for sameness, fear of aversive consequences like vomiting or gagging, etc.).

If you’re also seeking a registered dietitian, Wallace recommends conducting a discovery call before working with a new provider and asking them the following questions:

- “Have you worked with neurodivergent people before? Can you please tell me about your experiences?”

- “Do you understand how to work with someone who has sensory sensitivities, a lack of interoception, or specific needs surrounding routines or schedules?”

- “Do you treat ARFID?” and more importantly, “Do you enjoy working with people with ARFID?

“Overall, the right provider for you is someone whom you feel you can be honest with,” says Wallace. “Someone who will listen to your experiences, and who will treat you as a member of the team.”

While it may require extra legwork, finding an autism-informed provider will benefit you in the long run, because one-size-fits-all ED treatment often backfires on autistic patients. Dr. Fraley notes that autistic patients, especially those dealing with ARFID, should be wary of ED treatment approaches like meal-plan compliance models because they “can create power struggles that increase shame and avoidance.”

Eating disorder recovery will not be sustainable if providers don’t simultaneously address their patients’ autistic traits.

The bottom line

Common autistic traits, like sensory processing differences, a need for predictability/routine, and low interoception, can indeed have a significant impact on eating habits. But just as autism is a spectrum, the same can be said for whether or not eating challenges will develop into an eating disorder.

Autism-related eating challenges are not a mark of shame. This is why it’s imperative—especially if you believe you need eating-disorder treatment—to seek out autism-informed care. You deserve ED treatment that not only acknowledges your autism but also provides the necessary accommodations.

“There is room to incorporate different needs,” assures Dr. Fraley (though she notes that “there is also room for continued growth as a field”). If you need a higher level of care, such as residential or inpatient treatment, she recommends having an outpatient provider who understands eating disorders and can help advocate for you.

Whether you’re dealing with autism-related eating challenges or believe you might need eating-disorder treatment, Prosper Health is here to help. Our virtual, neurodiversity-affirming therapy services provide mental health support for autistic and neurodivergent adults—plus, they’re covered by insurance, making care more affordable.

You shouldn’t have to address your eating challenges and/or eating disorders alone.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

Is there a connection between eating disorders and autism?

Research shows a high co-occurrence of autism and eating disorders (EDs) among autistic women (or AFAB). Eating challenges are common among autistic people, as sensory processing differences, a need for predictability/routine, and low interoception can significantly affect eating habits. These eating challenges sometimes develop into eating disorders, but not always.

Do people with autism struggle with eating?

Autistic people sometimes struggle with eating due to sensory processing differences (issues with certain textures, flavors, temperatures), a need for predictability and routine (which results in wanting to eat the same foods), stress from autistic burnout, and low interoception (an inability to read hunger/fullness cues).

What eating disorder is associated with autism?

Avoidant-restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is closely aligned with autism, as many people with ARFID are either autistic or neurodivergent. The difference between ARFID and other EDs, like anorexia nervosa, is that people with an ARFID diagnosis are not hyperfixated on losing weight or their body image.

Is ARFID just autism?

No, ARFID isn’t “just autism.” It’s a completely separate diagnosis, and it is classified as an eating disorder. But it does often co-occur with autism because there are several overlapping traits, including strong food sensory sensitivities and preferences.

Sources

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/women-autism-spectrum-disorder/202109/why-so-many-people-autism-have-eating-disorders

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autism-and-food

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/interoception

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/sensory-processing-disorder-spd

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9545673

https://www.uclahealth.org/news/article/picky-eating-vs-arfid-how-tell-difference

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11891632/

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/arfid-and-autism

https://www.advancedautism.com/post/predictability--the-key-that-allows-your-child-with-autism-to-thrive

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/ocd-vs-autism

https://neurodivergentinsights.com/autism-interoception

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autistic-burnout

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/women-autism-spectrum-disorder/202109/why-so-many-people-autism-have-eating-disorders

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0149763424001866

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/alexithymia-and-autism

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autism-in-adult-women

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178124005705

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anorexia-nervosa/symptoms-causes/syc-20353591

https://www.autistica.org.uk/what-is-autism/eating-eating-disorders-and-autism

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/sensory-overload-in-autistic-adults

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autism-meltdowns

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9794-anorexia-nervosahttps://www.cedars-sinai.org/stories-and-insights/expert-advice/what-is-intuitive-eating

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autism-masking

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/9795-bulimia-nervosa

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17652-binge-eating-disorder

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autism-vs-adhd

https://chadd.org/adhd-news/adhd-news-adults/brain-reward-response-linked-to-binge-eating-and-adhd/

https://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/eating-disorders-autism

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/pathological-demand-avoidance

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11861872/

.webp)