Key Takeaways

- The term "high-functioning autism" can be considered outdated and harmful. While intended to refer to low support needs autism, it is not a clinical diagnosis. It creates a hierarchy within the autism spectrum based on performance of "normalcy".

- The preferred language focuses on support needs. The DSM-5 replaced functioning labels with levels of autism (Level 1-3 support needs), which more accurately indicates that environment can shift support needs.

- Masking is a common, but exhausting, behavior. Many autistic adults labeled "high-functioning" are actually masking (hiding) their traits to pass as neurotypical, which can lead to negative repercussions like autistic burnout.

- Affirming language makes a difference. Alternatives like "autistic person," "autistic person with low support needs" are recommended to focus on accommodations.

As our understanding of the autism spectrum evolves, so does the language associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). And that language matters.

Right before my daughter was diagnosed with ASD, I felt like everyone around me was using the phrase “high-functioning autism” to describe her relatively moderate support needs. It also seemed to confirm why it took several years to receive an autism diagnosis at all. I soon learned, however, that describing someone with “high-functioning autism” was not only incorrect but harmful.

For starters, “high-functioning autism” isn’t even a clinical diagnosis, though the term is pervasive enough that some people may mistake it for one.

What the best-intentioned people usually mean when they say “high-functioning” is Level 1 or low support needs, which often refers to someone who needs circumstantial support with social communication and restricted or repetitive patterns of behavior and interests (RRB).

Specifically, that can mean help with managing the need for sameness, recognizing neurotypical social functioning and cues, and managing sensory sensitivities. Autistic people who are Level 1 may also engage in masking, which can make someone seem to have fewer support needs than what is actually sustainable.

Nasiyah Isra-Ul (they/she) is an autistic professional and disability advocate who believes that the once-prevalent “high-functioning autism” label prevented them from receiving the support they needed throughout their childhood and young adulthood. It could also explain why they received a late autism diagnosis as an adult.

If you’re curious about signs of high-functioning autism in adults, you’re in the right place! But we won’t be using that problematic term, and neither should you. In this article, we’ll explain why the term is outdated, what people actually mean by it, and what the most common autistic traits look like for adults with Level 1 autism support needs or who mask heavily.

What 'high-functioning' autism means and why it’s problematic

According to Kristen Delventhal, LCSW, the term "high-functioning autism" (HFA) emerged informally in the 1980s–1990s as clinicians and researchers tried to describe verbal autistic individuals who did not have an intellectual disability and often had average or above-average IQ scores. At the time, people with Asperger’s were often viewed as “high-functioning.”

Although the updated DSM-5 replaced functioning labels with levels of autism (specifically, Level 1–3 support needs) in 2013, the “high-functioning” term does persist today—and not in a good way.

“The term ‘high-functioning autism’ is extremely harmful,” says Isra-Ul. “It creates a hierarchy within autism based on how well someone performs ‘normalcy.’” People would assume from a “high-functioning” label that those particular autistic individuals “were more intelligent, needed little to no support, and were just ‘a little weird.’”

Those (incorrect) assumptions meant that “it was harder for ‘high-functioning’ autistic individuals to be seen, heard, or supported when they struggled,” continues Isra-Ul. “It allowed all autistic individuals to be ranked and neglected based on societal preferences of normalcy and performance.”

One of the possible reasons the “high-functioning autism” label still finds its way into the conversation is that the DSM-5 “uses a lot of language around the term ‘functioning’ in diagnosis,” explains Anna Kroncke, PhD, a licensed psychologist with Prosper Health. “For most diagnoses”—including autism—“it is necessary for an individual to experience what we call ‘functional impairment’ or an impact on day-to-day life and functioning to meet criteria for a diagnosis.”

This is why diagnosis levels – instead of “high-functioning”—is the preferred language when describing an autistic person’s support needs. Someone with Level 1 autism, for example, may fit Dr. Kroncke’s “high-functioning” description, but still requires support with social communication and restricted or repetitive patterns of behavior and interests (RRB), which are specific traits of autism in adults.

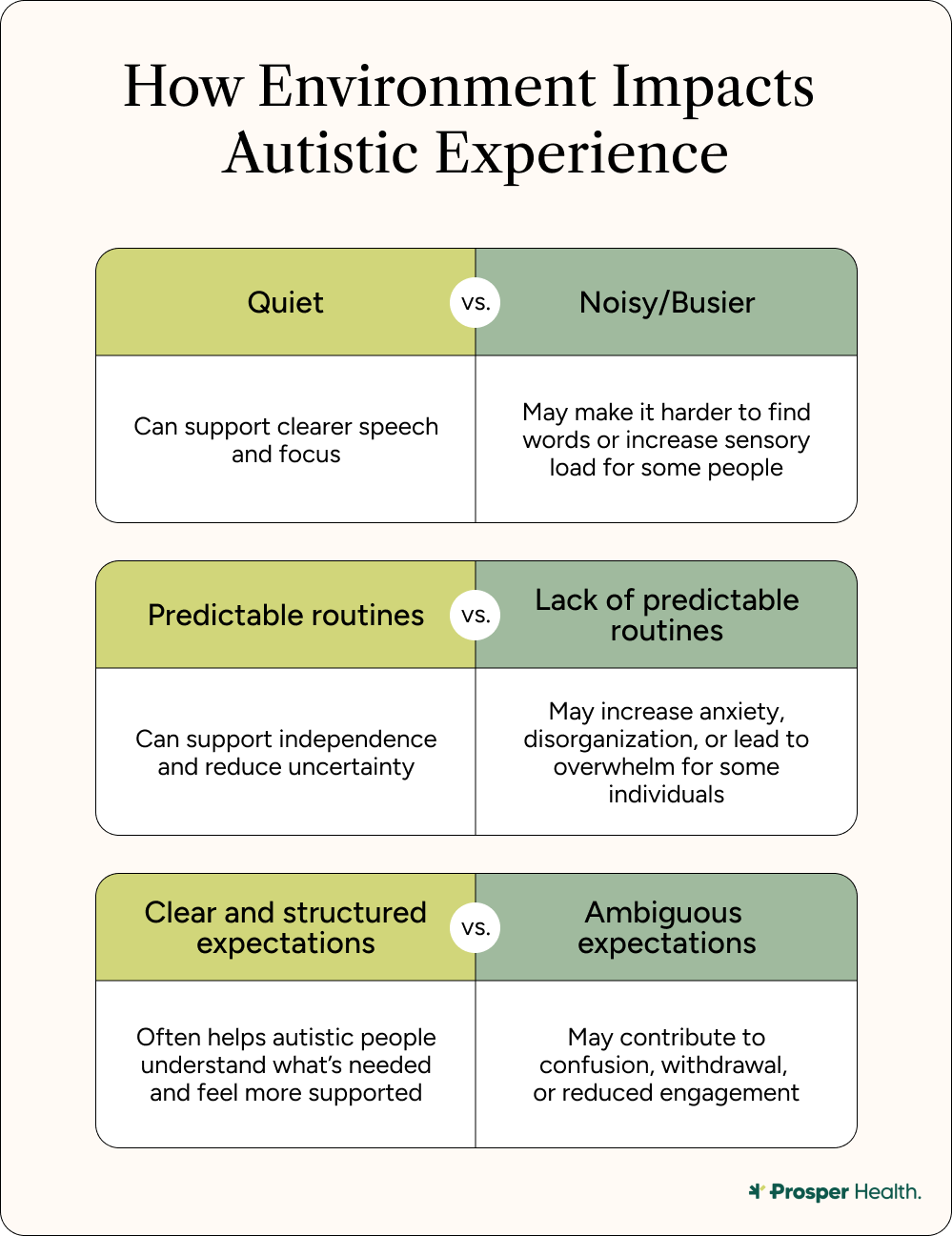

Autistic “functioning” is dependent on environment

But people with autism have support needs that vary across different contexts, certainly not at a fixed “functioning” level. The “high-functioning” label doesn’t consider “all of the facets of who a person is,” continues Dr. Kroncke. Instead, it’s a “blanket” label that defines their experience.

“Autistic functioning depends heavily on how demanding or supportive an environment is,” clarifies Delventhal. If someone is labeled “high-functioning,” this classification could potentially ignore invisible traits of autism in adults such as executive functioning, sensory overload, and mental health challenges. Delventhal offers the following examples of how someone’s “functioning” level can fluctuate depending on their environment:

Quiet vs. noisy settings: A person might speak clearly and focus in a calm office, but lose their words or shut down in a crowded cafeteria due to sensory overload.

Predictable vs. unpredictable routines: When schedules are consistent, an autistic person may appear “independent.” When plans change suddenly, they can experience anxiety, disorganization, or meltdowns.

Structured vs. ambiguous expectations: In structured tasks (like data entry or lab work), an autistic person may thrive; in unstructured networking or group projects, they freeze or withdraw.

How to reframe ‘high-functioning’ autism

“High-functioning” autism is often used to describe individuals who are “highly verbal in their communication, have an average or advanced vocabulary, as well as an average or advanced overall intelligence,” says Dr. Kroncke. The trouble with this description is that it’s reductive. These adults may appear independent, but they’re likely experiencing hidden struggles.

To that point, Delventhal further explains that an autistic person who is deemed “high-functioning” may in fact be someone who “‘passes’ as neurotypical in social settings” through masking autism, which is the practice of hiding certain behaviors like stimming.

“When I am masking, I can appear highly adaptable and more socially fluent," confirms Isra-Ul. Though their high-masking autism has produced negative repercussions: “Masking required me to hide my autistic behaviors, try to appear more 'normal,' and stress over expectations, to my own detriment.”

So how can we reframe the term “high-functioning” autism?

Dr. Kroncke recommends refocusing the conversation on a person’s specific support needs, while Delventhal emphasizes the importance of “descriptive language, not hierarchical labels.”

Delventhal also suggests these practical language alternatives to “high-functioning autism”:

- Autistic person

- Autistic person with low support needs

- Autistic person requiring Level 1 supports

- Autistic person who communicates verbally, or who is independent in daily living

By focusing more on accommodations rather than social acceptability, switching to more affirming language can make a significant difference for autistic individuals, whether in the workplace, in relationships, or during interactions with healthcare professionals.

“Language shapes perception,” observes Delventhal. “Words influence bias.” She further explains that if a clinician, coworker, or partner hears terms like “low-functioning” or “disordered,” “it frames the person as broken or deficient.” But contrast that with referring to someone as either an “autistic person” or a “person with high sensory sensitivity” instead. Doing so “frames autism as a valid neurotype with unique needs.”

“Many autistic individuals have very passionate interests and can love their career if they are given the support needed to accommodate for sensory or communication needs,” says Dr. Kroncke.

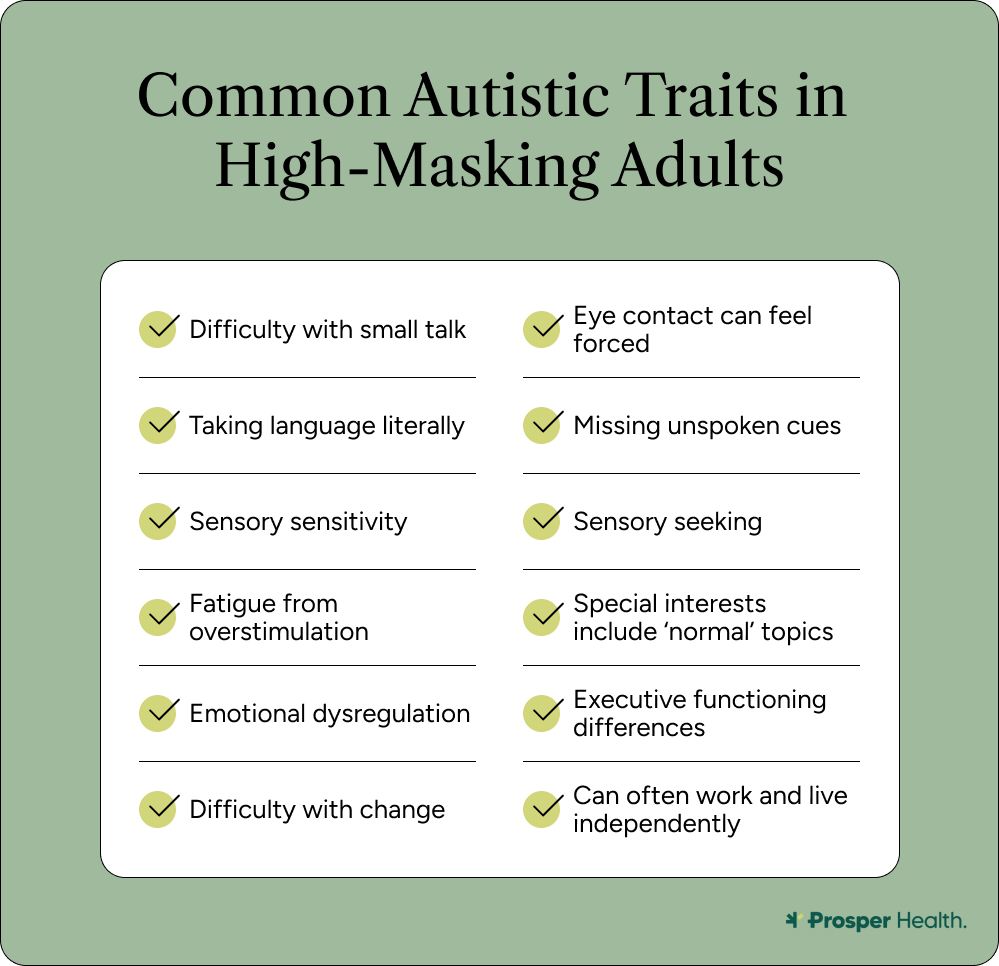

Common traits of autistic adults who mask or have lower support needs

It’s essential to remember that autism is a spectrum, and traits will vary by individual.

But in terms of Level 1 or low support needs, Dr. Kroncke says people “generally have more subtle autistic traits that may not be readily identified to the casual observer.” They tend to have more adaptive skills and independence, can often hold down employment, and can manage their own finances without needing more regular support from family or caregivers.

Below, however, are some examples of autistic traits in adults who might’ve been labeled “high-functioning,” courtesy of Dr. Kroncke and Delventhal:

- Limited use of small talk

- Forced eye contact

- Taking language literally

- Preference for clear, direct communication

- Sensory sensitivity

- Sensory seeking

- Fatigue from overstimulation

- ‘Socially acceptable’ special interests

- Emotional dysregulation

- Executive functioning differences

- Difficulty with change

Social and communication patterns

- Difficulty with small talk. Some autistic people may prefer or be adept at talking at length about a specialized area of expertise or passion instead of engaging in various other topics.

- Eye contact/body language. Eye contact can be uncomfortable or distracting for some people. Certain facial expressions or gestures “might appear flat or mismatched when compared to neurotypical expectations,” says Delventhal.

- Taking language literally. Some autistic people often “may not perceive sarcasm and joking,” says Dr. Kroncke. Instead, they prefer “more direct or clear communication.”

- Missing unspoken cues. Communicating nonverbally and reading others’ nonverbal communication patterns is not very natural for some autistic people, says Dr. Kroncke.

Sensory processing and regulation

- Sensory overload. Autistic individuals “tend to have trouble tolerating sounds, textures, smells, and can be more sensitive than those around them,” says Dr. Kroncke.

- Sensitivity to sensory experiences. Things like bright lights, background chatter, buzzing electronics, perfume, or certain clothing textures “can be overwhelming” for autistic people, says Delventhal.

- Interoception difficulties. While not outwardly apparent to others, some autistic people have trouble perceiving internal emotions (anger, sadness) or physical sensations like hunger. This can significantly impact day-to-day functioning.

- Sensory seeking. On the flip side, autistic individuals tend to be more sensory-seeking than those who are neurotypical. They might seek out deep pressure, rhythmic motion, or certain sounds/textures through tools like weighted blankets, rocking back and forth, or specific playlists.

- Fatigue from overstimulation. When an autistic person is overstimulated, they “may withdraw, become nonverbal, or experience intense emotional or physical reactions,” says Delventhal.

Emotional and cognitive experiences

- Special interests. These are intense fascinations that provide “comfort, meaning, and motivation” for autistic people, explains Delventhal. Sometimes, these special interests can become professional expertise.

- Emotional dysregulation. Since every autistic person experiences emotion and emotional intensity differently, they may struggle to modulate emotional expression, which can result in meltdowns or shutdowns.

- Executive functioning differences. Time management, task initiation, and transitions can be challenging for people with autism. Functional tools like visual schedules, reminders, and routines help maintain stability.

- Change and uncertainty. For some autistic people, “sudden changes in plans or expectations can cause anxiety,” says Delventhal. Many autistic people thrive with predictability and clear communication.

Masking and burnout

- Chronic exhaustion. Meeting neurotypical expectations while socializing or at work can lead to autistic burnout, which looks like profound exhaustion, decreased functioning, and increased sensory/emotional sensitivity.

- Identity confusion. When autistic people spend so much time and energy masking to feel accepted among their neurotypical peers, it can then be difficult to determine who they are “under the mask,” so to speak.

- Difficulty relaxing. It’s hard for autistic people to relax in situations when masking because they may be practicing conversational scripts in their head, or forcibly making eye contact to appear “normal.”

- Difficulty unmasking. Conversely, some autistic people have been masking for so long that it’s become second nature, and therefore challenging to just stop.

When to consider an autism evaluation

There are several potential signs of autism in adults which can suggest a formal autism evaluation would be helpful. They include consistently experiencing challenges with “social interaction, understanding [other people’s] communication, perspectives, and social cues, feeling misunderstood, and a need for sameness and routine that impacts their lives and relationships with others,” says Dr. Kroncke.

Even if you’ve learned to compensate well—which is a common trait of autism in women—that’s no reason not to explore a diagnostic assessment. As Delventhal points out, compensating for autism traits can be “distressing or exhausting.”

If you’re considering getting tested for autism as an adult, Prosper Health can help. You can expect a neurodiversity-affirming environment consisting of several standardized assessments, as well as a clinical interview.

Regardless of the outcome, whether or not you receive a late adult autism diagnosis, how you self-identify is not only your choice, but your right. Prosper Health is here to guide you on that journey, either through an autism assessment, therapy, or community support.

The bottom line

People who are considered to have Level 1 autism may have less-visible needs (although this can vary by individual), but that doesn’t mean they don’t require support.

Language matters. Period. The less we use harmful terminology, the quicker it will go out of style. And that includes labels like “high-functioning” autism.

For Isra-Ul, letting go of the “high-functioning” term has been nothing short of empowering: “Learning to unmask and recognize that there is no need to achieve ‘high-functioning’ has been the best decision I've ever made." Doing so has allowed Isra-Ul to "be proud of my autistic mind and be okay with the fact that I may need more support than people would expect, which better suits my needs.”

The danger of terms like “high-functioning” is that it “implies we don't struggle,” declares Isra-Ul. Not only that, they continue, but such labels “can dehumanize our existence.” Removing these types of hierarchical labels “allows autistic people to seek support without feeling shame, and allows us to exist without performing neurotypical behavior for societal acceptance.”

When in doubt, just stick to fact-based terms like “autistic person.” It’s short and to the point.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

What should I say instead of “high-functioning autism”?

Focus more on the newer Level 1–3 diagnostic classifications, and use language that reflects an autistic person’s support needs rather than a hierarchical label:

- Autistic person

- Autistic person with low support needs

- Autistic person requiring Level 1 supports

Why is the term “high-functioning autism” offensive?

The term may acknowledge an autistic person’s intelligence, independence, and vocabulary, but it doesn’t recognize their more subtle support needs. People diagnosed with Level 1 autism still require support with social communication and restricted or repetitive patterns of behavior and interests (RRB), like stimming.

What is level 1 autism?

Level 1 autism means someone requires support in social communication and restrictive and repetitive behavior. People can be different levels for different aspects of functioning, even though diagnostically, people tend to be assigned a single level. That said, people with a Level 1 autism diagnosis will likely need support with things like:

- Recognizing neurotypical social functioning and cues

- Executive functioning

- Managing sensory sensitivities

- Managing autistic behaviors like special interests and stimming when in social settings

Why is “high-functioning autism” no longer used?

There’s been a concerted effort to move away from the term “high-functioning autism” because those in the autism community feel it dismisses their very real, albeit subtle (and sometimes invisible), support needs.

What is “high-functioning autism” called now?

There are several affirming terminology options to refer to an autistic person who, in the past, might have been called “high-functioning.” You can’t go wrong sticking to fact-based diagnoses, like:

- Level 1 autism – requiring support

- Level 2 autism – requiring substantial support

- Level 3 autism – requiring very substantial support

Other options include:

- Autistic person

- Autistic person with low support needs

- Autistic person requiring Level 1 supports

Sources

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/what-is-autism-spectrum-disorder

https://health.clevelandclinic.org/high-functioning-autism

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-97698-000

https://www.kennedykrieger.org/patient-care/conditions/restrictive-and-repetitive-behavior

https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autism-meltdowns

https://existentialpsychiatry.com/what-is-high-functioning-autism/

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autistic-burnout

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/what-are-the-levels-of-autism-support

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autism-masking

https://www.ndpsych.com/blog/autism-misdiagnosis-challenges-for-healthcare-professionals

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autism-and-stimming

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/women-autism-spectrum-disorder/202003/can-you-do-small-talk-when-you-have-asd

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10123036/

https://health.clevelandclinic.org/sensory-overload

https://www.buildingblockstherapy.org/blog/addressing-sensory-seeking-in-autism

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/special-interests-and-autism

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10544895/

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autism-meltdowns

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/executive-function

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4869784/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10060524/

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/adult-autism-signs

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/how-to-get-tested-for-autism-as-an-adulthttps://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/neurodiversity-affirming-therapy

.webp)