Key Takeaways

- Masking autism is the concealment of autistic traits to appear more neurotypical, often for social acceptance or safety, but it can be mentally and physically exhausting.

- Different forms of masking include camouflaging, mirroring, and mimicking

- Masking can lead to significant mental health issues, such as anxiety, depression, identity confusion, and autistic burnout.

- Gender, race, and sexuality can influence the nuances and pressures of masking. Women and people of color are more likely to experience this pressure.

- Unmasking is the process of reducing or stopping masking behaviors to live more authentically. Still, it requires courage, support, and a safe environment.

Imagine you’re hanging out with a group of friends. On the outside, this scenario looks like a typical get-together: Everyone is laughing, making eye contact, and visibly comfortable with one another.

But for some people, there is a very good chance that much of their behavior is the result of masking, or a concealment of their autistic traits. Sure, these people may come off socially at ease, but a debilitating dance is taking place behind their eyes.

“After I've been hanging out with people, I need to take a nap for one to two hours…my brain literally needs to shut off. I feel like a computer that needs to reboot,” says Aura Marquez, an author living with autism.

Marquez says she’s been masking since she was in late elementary school: “It’s gotten to the point where I can’t turn it off.”

Masking autism is how many neurodivergent people navigate a neurotypical world, so it’s important to understand the reasons behind this practice in order to minimize stigma. While masking may provide some benefits, it’s important to also remember the toll this behavior takes on one’s mental health.

That why learning how to also unmask, under the right conditions, is essential to helping autistic people feel comfortable in their own skin. This article will explore options for those who wish to stop masking, as well as support for those who do mask.

What is autistic masking?

Masking in autism is presenting yourself in a way, either consciously or unconsciously, to fit in better in a neurotypical world. It can mean forcing eye contact with others (when that’s not a natural or comfortable characteristic) or suppressing your self-soothing behaviors like stimming.

In essence, masking is a way autistic people hide their true selves to avoid negative judgment or to be safer in social settings.

In fact, some neurodivergent people have become so “especially skilled at hiding or compensating for their autistic traits,” notes Kristen Delventhal, LCSW, a psychotherapist and sibling to an autistic woman, that their behavior is considered high-masking autism. They are so adept at suppressing their traits, observes Delventhal, “to the point that others don’t even realize they’re autistic at all.”

Some other behavioral terms under the neurodivergent masking umbrella include:

- Camouflaging: This is the practice of copying behaviors and masking certain personality traits depending on the social situation. Basically, camouflaging in autism is “hiding your autistic traits to fit in,” says Delventhal.

The next two terms describe the “different social processes” behind certain masking decisions, explains Delventhal:

- Autism mirroring: This is a typically unconscious and reciprocal process. As such, it can be “mentally exhausting” for people with autism.

- Autism mimicking: Autism mimicking behavior is more deliberate and imitative. Autistic people are purposefully copying behaviors and phrases so they can fit in with others.

Why do autistic people mask?

For Marquez, masking was a means of survival: “I have worked for years to act neurotypical because I was bullied so badly,” she says.

While the reasons for masking vary by individual, Delventhal explains that this practice is “typically a protective, adaptive response—not a sign of deception or inauthenticity.”

Masking can help autistic people feel “safe, accepted, or successful in environments that don’t naturally support their needs,” observes Delventhal. The settings may necessitate certain behavioral modifications, but ultimately, social masking is an attempt to feel a sense of belonging. It is also a survival mechanism in a society that discriminates against autistic people.

The following scenarios and corresponding common camoflauging examples are provided by Debra Kissen, Ph.D, a licensed clinical psychologist and the CEO and founder of Light on Anxiety CBT Treatment Centers:

- School: Hiding your stims or pretending to understand group work as a way to avoid bullying.

- Work: Suppressing your sensory needs (not wearing noise-canceling headphones, forcing eye contact) to appear “professional.”

- With family: “Acting normal” or engaging in mirroring or mimicking to avoid disappointing parents or siblings.

- In friendships/dating: Giving off an “easygoing” appearance, even if the social plan is overwhelming.

- In medical settings: Masking your neurodivergent traits to be taken seriously by a provider who may misinterpret autistic communication.

Masking autism in these scenarios may achieve certain relationship goals, but not without consequence: “Unfortunately, society rewards masking behaviors as ‘compliance,’ observes Delventhal.

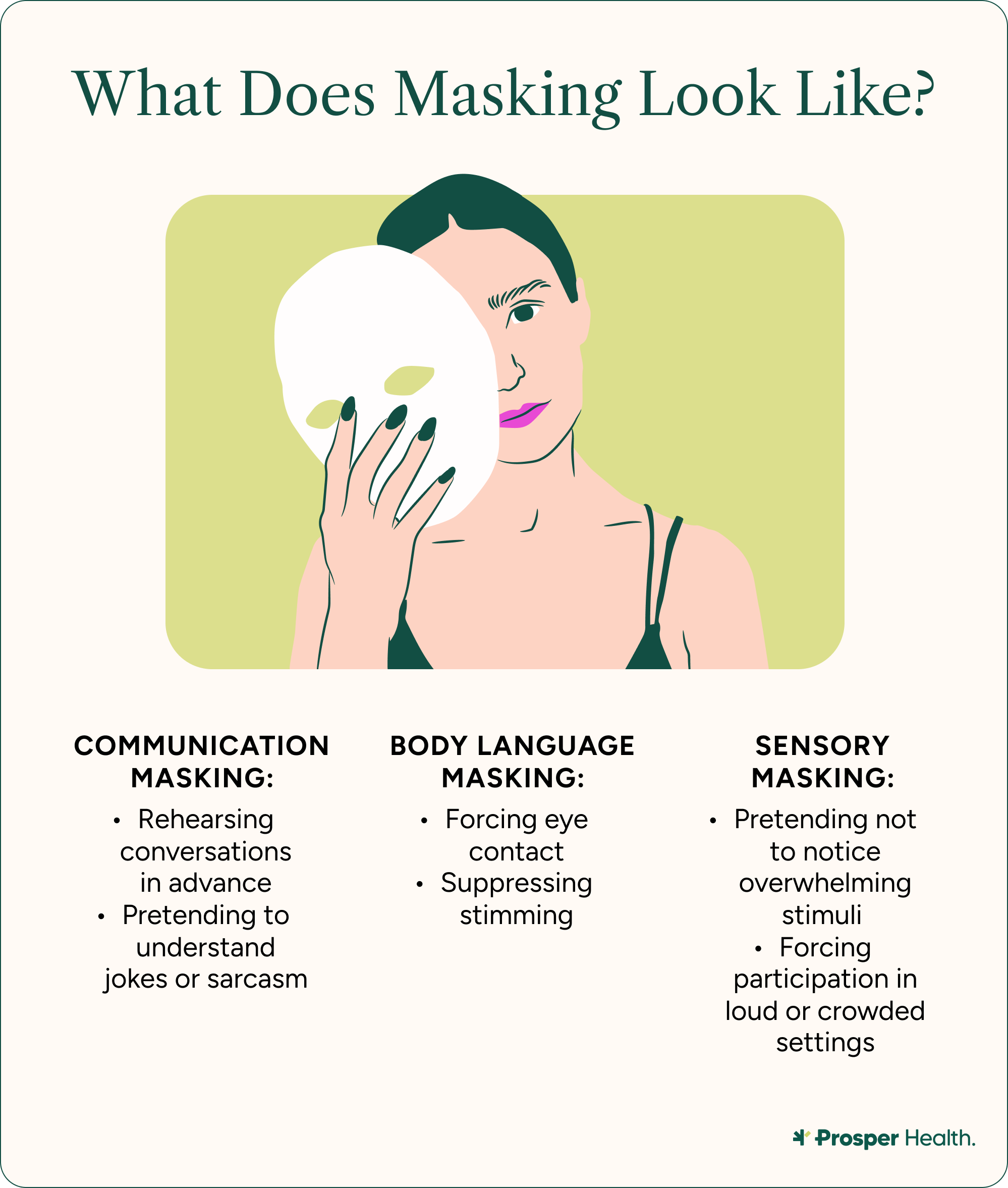

What are examples of autistic masking behaviors?

Autism masking examples vary by individual and by setting. Rather than falling into just a few broad categories, masking behaviors can occur across all seven domains of autism characteristics, which are organized under two main criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5): social communication and restricted/repetitive behaviors.

Social communication

Social communication is an umbrella term covering the use and understanding of spoken and non-spoken communication. This can include conversation, body language, and various social exchanges such as sharing and shaking hands.

Social-emotional reciprocity

Social-emotional reciprocity refers to the back-and-forth of social interaction, like sharing emotions, responding to others, and generally feeling like you know what to say and do naturally in communication.

Examples of masking in this category, according to experts like Delventhal and Dr. Kissen, can include:

- Copying tone, slang, or humor to match others

- Rehearsing small talk or entire conversations in advance

- Pretending to understand jokes or sarcasm

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication is all the ways we convey messages without using words—like body language, facial expressions, gestures, eye contact, posture, and tone of voice. In this category, examples of autistic masking are, understandably, more physical:

- Forcing eye contact (even if it’s uncomfortable or distracting)

- Copying facial expressions or gestures

- Sitting in a posture that’s uncomfortable to you to appear “relaxed”

Marquez admits she engages in many forms of body language masking: “I pretend to look at people’s eyes,” she says. Plus, Marquez has developed “emotions and expressions that aren’t real, but I’ve trained myself to do them.”

Relationships

Relationships in the context of autism refers to the ability to develop, maintain, and understand social connections with others, particularly peers.

Masking in these settings can appear as:

- Social "chameleon" behavior: Adapting personality, interests, or reactions to match those around them

- Pretending to understand the difference between a coworker and a friend

- Forcing yourself to socialize more often than you would actually like to hide minimal social needs

Restricted and repetitive behaviors

Restricted and repetitive behaviors are a variety of movements and activities identified by repetition, inflexibility, and predictability.

Repetitive motor or speech behaviors

Repetitive behaviors are actions, movements, or speech that are repeated over and over and often serve a regulatory, sensory, or comfort function, but can also serve other means.

Common ways to mask repetitive behavior include:

- Swapping hand-flapping, rocking, spinning, or pacing for playing with hair or fidgeting with hands behind the back

- Suppressing stimming (fidgeting, rocking, hand-flapping)

- Lining up toys, spinning wheels, or repeatedly opening/closing objects in private so it is not noticeable

- Engaging in echolalia or echolalia-like activity in your head

Marquez admits she engages in many forms of repetitive behavior masking. She's "created stims that aren't noticeable." These include doing her hand stimming and her echolalia (a type of stim where you repeat words spoken by someone else) "in my mind."

Need for routines and sameness

Many autistic people have a strong preference for predictable patterns, order, and consistency, along with differences in how they process and handle change or transitions.

Common ways to mask a need for routines and sameness include:

- Pretending to be okay if a friend says they are going to arrive at 12:15 PM at your home and they have not arrived yet at 12:27, or they arrive at 12:10.

- Waiting for a spouse to go to work so you can remake a bed or reorganize a cabinet without them noticing because they did not do it the correct way.

- Hiding the fact that you looked up a new doctor's office on Google Maps, walked from the parking lot to inside the building with Google Maps, checked out pictures and reviews to get the office layout, checked out what people who worked there look like ahead of time, and practiced going there the week prior with a close loved one.

Intense and/or unexpected interests

Intense or unexpected interests in autism are when someone shows highly focused interests or passions that stand out in intensity, focus, or topic compared to peers.

Some ways to mask this are:

- Pretending to like things common among peers when you have no interest in them whatsoever.

- Hiding things around your house that are your interests, if you are having guests over.

- Preventing yourself from telling a friend all about your preferred interests.

Sensory processing

Autistic people who are affected by certain sensory processing issues may mask these traits as well:

- Pretending not to notice overwhelming sounds, smells, or lights

- Forcing participation in loud or crowded settings

- Wearing uncomfortable clothing (e.g., formal attire, itchy fabrics) to meet social expectations

- Avoiding sensory tools (earplugs, sunglasses, stim toys) out of embarrassment

How does masking affect mental health outcomes?

While masking can help neurodivergent individuals navigate the world through relationships with neurotypical people, there are several long-term drawbacks to the practice.

“[Masking is] exhausting,” reiterates Marquez. “It's physically and emotionally painful.” Not only does Marquez suffer from autism masking burnout, she’s also unable to publicly present her authentic self: “People don't think I'm autistic because I can no longer unmask, but my brain is very much struggling constantly.”

From a clinical perspective, experts like Delventhal and Dr. Kissen confirm that masking autism can cause significant mental health issues, such as:

- Emotional and physical exhaustion (aka autism burnout)

- Anxiety and depression

- Identity confusion (“Who am I when I’m not masking?”)

- Delayed or missed diagnosis (since traits are hidden)

How do social identities affect masking?

No matter who you are, every variable of your identity will “impact the nuances of masking,” says Delventhal. This is because “each group and identity already has nuances related to the way they interrelate and appear in the world.” Regardless of your race, gender, and/or sexuality, “there are many unspoken rules for these subgroups that can impact the level of awareness and mental load taken on by an autistic person to maintain a sense of being typically part of each group.”

So, weird as it sounds, pretty much everything that makes you unique will affect how you mask. Dr. Kissen also highlights that this can include any socioeconomic pressures, cultural expectations, and workplace norms, because they “all shape how much someone feels they must mask.” Even though social identity and masking tend to be individualized practices, it’s still worth examining the nuances by major category to better understand why certain groups of people feel the need to mask.

Gender

Studies have found that autistic girls and women feel more pressure to fit in via camouflaging due to gender-based societal expectations: “Girls and women are more likely to mask to meet social norms of being ‘polite’ and ‘social,” observes Dr. Kissen. As previously discussed, the higher tendency of females engaging in masking can explain the increased rates of missed or late diagnosis among this group.

While autism masking in males does occur, studies show that masking is far more prevalent among females, including those who are considered high masking autistic women. However, males are diagnosed with autism three to four more times than females, suggesting that masking does have an impact on the timely diagnosis of women with autism.

Race

Unfortunately, autistic people of color are underrepresented in autism research and underserved in their communities. For those reasons alone, it’s not surprising that “autistic people of color may mask to protect against both racism and ableism,” says Dr. Kissen. Many BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) already feel the need to engage in strategies like code-switching (modifying their behavior and language to conform to white-dominated society), for their own safety. If they’re also neurodivergent, there is an equal pressure to mask their autistic traits as well.

Sexuality

Autistic people are more likely to be members of the LGBTQ+ community. As such, they engage in masking for their own protection and self-preservation—especially those who identify as trans. Given the increased stigma and judgment toward trans individuals in recent years, masking has become a necessary safety tool. A study conducted by SPARK backs up these developments, finding that autistic adults who are sexual minorities masked their autistic traits more often than those who are heterosexual.

What is unmasking?

Autism unmasking is the process of “reducing, stopping, or becoming more aware of masking behaviors,” explains Delventhal. By engaging in unmasking, a neurodivergent person can begin living in ways “that align with [their] true needs, communication style, and sensory comfort,” says Dr. Kissen. “It’s about authenticity and self-acceptance.”

It’s important to note here that choosing to unmask does not mean you are “‘letting go’ of professionalism or social skills,” says Delventhal. “It’s about honoring one’s true self after years (or decades) of trying to fit into a neurotypical mold.”

That’s not to say unmasking isn’t without its challenges: “When I have unmasked in front of people that aren't safe, I've been laughed at and made fun of,” Marquez shares. “I've been told I'm exaggerating or making it up.”

There is a very real “fear of rejection or misunderstanding,” says Dr. Kissen, as well as a “risk of losing jobs, relationships, or safety.” Also, she says, it’s difficult for autistic people to know what feels “authentic” after masking for so many years.

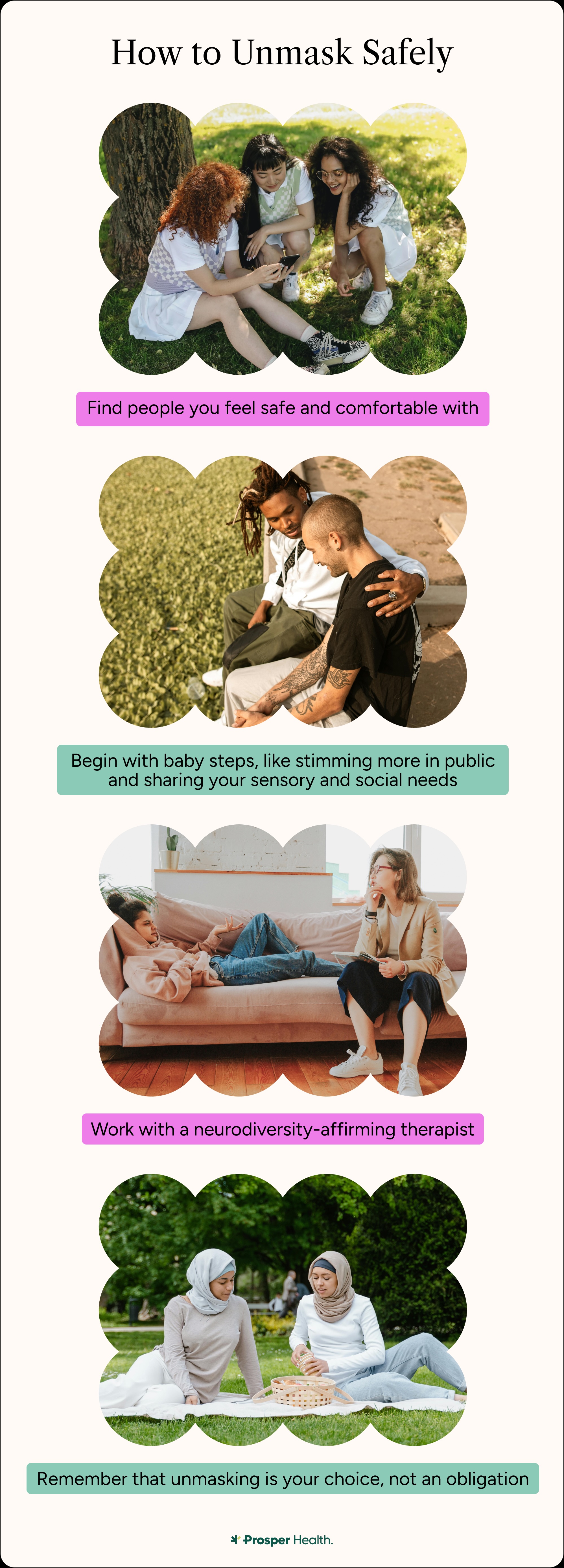

Practical strategies for unmasking

If you are contemplating unmasking, the first thing to remember is that this is your choice, not an obligation.

Baby steps are the name of the game here, finding a balance with people you trust: “Authenticity within safety,” says Delventhal.

Dr. Kissen recommends experimenting with unmasking in safe spaces, such as with trusted friends or online neurodivergent groups. This can start with stimming around others, in the form of small gestures, like tapping or doodling. She also suggests practicing communicating your needs with others (“Loud environments overwhelm me”) and working with a neurodiversity-affirming therapist.

Since masking can become an ingrained practice, Marquez advises addressing the issue with younger generations as early as possible: “Don’t force your kids to mask,” she says. “It will cause a lifetime of anxiety and depression.” She suggests “talking to friends and family so they all accept your child as they are and respect their needs,” and even offering to visit the child’s classroom to teach students about autism.

Supporting autistic people who mask

Since the decision to mask (or unmask) is a personal one, what neurodivergent people need above all is support, whether it’s from a loved one or a work colleague.

“Let them know they can unmask if they want to when they’re with you,” says Marquez. “Never laugh, question, or mimic a person’s traits.” Above all, she says, “Do not treat an autistic person differently, no matter what their support needs are.”

If you’re a friend or family member, “believe [an autistic loved one] when they say something is hard, even if they look fine,” advises Dr. Kissen.

If you’re a supervisor or colleague, Dr. Kissen recommends “normalizing accommodations, providing clear written expectations, and allowing flexible communication styles.”

And above all, she says, “avoid pressuring someone to ‘act normal.’”

Comfort with masking and unmasking begins with neurotypical “normalizing differences” and “modeling acceptance,” says Delventhal. “When you embrace your own quirks, it signals safety for others to do the same.”

On an individual level, Marquez encourages neurotypical people to “educate yourself on what autism really is, what masking is, and what stimming is.”

While change begins with the individual, enacting systemic change within larger institutions like schools and employers doesn’t happen overnight. Marquez implores schools to “teach lessons about different neurotypes and traits,” and to “explain why people stim.” She also advocates for workplace accommodations like “[noise-canceling] headphones, fidgets, hoods, or certain [types of] dress.” Echoing that sentiment, Dr. Kissen suggests workplaces adopt disability-affirming hiring, sensory-considerate offices, flexible schedules, and anti-ableism policies.

The bottom line is, “autistic masking doesn’t happen in a vacuum,” says Delventhal. “It happens because environments communicate (often unintentionally): 'You’ll be accepted if you act neurotypical.’”

Change only happens when we, as a society, “shift the ‘if’ to ‘you’ll be accepted as you are.’”

That means validating neurodivergent people’s experiences, and making it safe to mask—or unmask—in anyone’s presence.

Getting support with masking

An autistic person’s relationship with masking is a fluid one, so if you’re thinking about unmasking or just seeking validation for why you mask, Prosper Health can help.

In addition to offering telehealth autism assessments, Prosper Health provides neurodiversity-affirming therapy to help you better understand common signs of autism in adults (which include masking).

More resources

If you’re interested in learning more about masking, how to start unmasking, or are trying to support a neurodivergent loved one, check out Delventhal’s recommended resources:

Books

- Autism and Masking by Dr. Felicity Sedgewick, Dr. Laura Hull, and Helen Ellis

- Unmasking Autism by Devon Price

- NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity by Steve Silberman

- Aspergirls: Empowering Females With Asperger Syndrome by Rudy Simone

Websites

- Autism Books by Autistic Authors is an online catalog offering a list of 13 books on masking autism

- The Autistic Advocate offers articles, research summaries, and community reflections on autistic masking here.

- Association for Autism and Neurodiversity (AANE) offers Masking: A Guide

- The U.K.’s National Autistic Society offers advice and guidance on masking

- Aide Canada’s Autistic Burnout Toolkit

- Autistic Masking Resources from autism specialist Jodie Clarke

- Kadiant.com: Resources for Understanding Masking

- Neurodivergencewales.org: “Masking”

Conclusion

Whether you’re someone who masks or is testing the waters of unmasking, you deserve validation and support for your decision. As Marquez already stated, masking is a form of survival, and no matter who you are, it is never a flaw.

At the same time, masking is exhausting, and autistic people deserve spaces where they can be their authentic selves. But the unmasking process can’t just happen on its own. It “takes courage, support, and safe environments,” says Dr. Kissen.

So if you’re thinking about unmasking, know that it is possible, and that help is out there.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What resources are available for people with autistic masking?

There are several books and websites available that offer masking explanations and tips for how to support autistic loved ones. Books include Autism and Masking by Dr. Felicity Sedgewick, Dr. Laura Hull, and Helen Ellis, and Unmasking Autism by Devon Price. Websites include Autism Books by Autistic Authors, The Autistic Advocate, and the Association for Autism and Neurodiversity (AANE).

What is autistic masking?

Autistic masking is the concealment of autistic traits to appear more neurotypical. Neurodivergent people engage in this practice for several different reasons, ranging from social acceptance to safety.

Is masking bad?

There is nothing inherently “bad” about masking, but the practice can be physically and emotionally exhausting for autistic people, and it prevents them from being their authentic selves.

Why do people mask?

The reasons why people mask vary by individual, but ultimately, masking is a form of survival in a neurotypical world. Autistic people mask to avoid bullying and to be accepted among their peers and workplace colleagues.

How can I start unmasking safely?

It’s important to find people you feel safe and comfortable with, and to begin with baby steps. This can mean stimming more in public or being more vocal about your needs regarding sensory issues or socializing in big groups. It’s also a good idea to work with a neurodiversity-affirming therapist who can help you understand the role masking plays in your life.

Sources

https://health.clevelandclinic.org/what-is-masking

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autism-and-stimming

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10060524/

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/autism-in-adult-women

https://www.prosperhealth.io/test/the-cat-q-questionnaire

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/echolalia

https://embrace-autism.com/consequences-of-autistic-camouflaging/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272735821001239

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10060524/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9908289/

https://sparkforautism.org/discover_article/rm-identity-masking/

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/neurodiversity-affirming-therapy

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/how-to-get-comfortable-stimming-around-others

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/adult-autism-signs

https://www.npr.org/2025/09/18/nx-s1-5445303/transgender-people-financial-anxiety

https://www.cabsautism.com/autism-blog/social-reciprocity

https://dictionary.apa.org/nonverbal-communication

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8280472/

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/special-interests-and-autism

https://www.prosperhealth.io/blog/how-to-deal-with-sensory-overload-in-autistic-adults

Related Posts

Meltdowns in Autistic Adults: Why They Happen, What They’re Like, and How to Live with Them

When many people hear the word “meltdown,” they might envision a kicking-and-screaming child, lashing out because their parent or caregiver said “no.”

While that is an accurate description of a typical child meltdown, a meltdown in an autistic adult is entirely different, and not to be confused. In fact, in many cases, meltdowns in autistic adults can look like the antithesis of a childhood tantrum. Instead of engaging in "why won't you give me what I want!?" goal-oriented behaviors that are synonymous with tantrums, autistic adults usually need to get away from people and into a calm, dark, safe space during a meltdown.

The most important thing to remember about an autistic meltdown is that it’s not a choice, but an involuntary nervous-system response to intense overload or stress. If someone is experiencing a meltdown, they are not intentionally acting out: They are dealing with complex emotions just like the rest of us, and don’t deserve the ongoing stigma that is attached to autism—and by extension, meltdowns.

Victoria Mindiola (they/theirs/she) is an autistic person who works as an inclusion consultant and educator, focusing on advocacy for neurodivergent students. When Mindiola experiences an autistic meltdown, they say they frantically need “to find a place that is safe and dark and quiet and empty of people.”

Unfortunately, the stigma around autism and meltdowns remains because adult-focused research and resources are still lacking. While there’s plenty of research available on autistic meltdowns in children, there is limited data from the perspective of autistic adults.

In this article, we’ll provide a comprehensive breakdown of autistic meltdowns in adults: What they are, why they happen, how to identify early signs, and how to support yourself or someone else.

.png)

What Is Stimming? A Guide to Autistic Self-Regulation and Expression

Self-stimulatory behavior, or "stimming", is a physical behavior used by autistic and other individuals (including those who are allistic) to regulate emotional or sensory stress, sensory seek, and/or express their emotions. In autistic people, stimming is often repetitive and is a way to calm their minds and bodies.

Personally, I have stimmed my entire life in many ways. Notably, I am always carrying a rolling stim toy with me. It helps to ground me when I get anxious, or when the noises in a room are too loud or overwhelming.

Everyone stims, whether they realize it or not. If you’ve ever bounced your knee while bored, or clicked a pen open and closed, you’ve stimmed. But for autistic folks, stimming serves a key role in sensory and emotional management. It’s not something to fix, but rather something to understand.

In this article, we’ll explain what stimming is, why it happens, and how to support yourself or someone around you who stims.

Sensory Overload in Autistic Adults: Why It Happens and How to Cope

For autistic and neurodivergent adults, sensory overload can feel like it hits all at once. Imagine you’re in a crowded restaurant. At first, the talking all around you becomes intrusive, and you can’t concentrate on the person across from you, no matter how hard you try. Then the sound of repeated clinking of glasses and forks on porcelain intensifies, grates at your nerves, and suddenly the smell of the woman’s perfume at the table next to you becomes overwhelmingly strong.

Suddenly, you’re in full-body panic mode because this combination of sensory experiences is simply too much. Allistic people are able to compartmentalize and block out these types of input, but autistic people often cannot.

Sensory processing differences—formerly referred to as a “sensory processing disorder”—are the variations in how the brain receives, interprets, and responds to information gained through your senses from the environment and the body. Autistic people’s sensitivity to stimuli will vary depending on the individual.

Sensory overload, on the other hand, can happen when a neurodivergent person’s brain becomes so overwhelmed by sensory information in an environment (think: sights, sounds, smells, textures) that their body goes into a state of panic and fight or flight mode.

“Sensory overload, or strong sensory input, can often be described as ‘physically painful’ or ‘making my skin crawl’ by autistic adults,” says Jackie Shinall, PsyD, head of reliability and quality assurance at Prosper Health. “For example, they don’t necessarily feel anxious or stressed by the input, but rather uncomfortable overall, especially physically.”

While anyone can experience sensory issues and sensory overload, they are especially common among autistic adults and neurodivergent people more broadly. In fact, a 2021 study published in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders surveyed autistic adults and found that 93.9% reported being extra sensitive to sensory experiences. Autism and sensory overload often go hand-in-hand.

If you have questions about sensory overload in autistic adults, you’ve come to the right place. In this article, we'll cover what sensory overload is, why it happens, what it feels like, and how to prevent and recover from it.

.webp)