Key Takeaways

- Sensory overload in autistic and neurodivergent people can happen when the brain becomes overwhelmed by sensory information in an environment.

- Sensory overload can leave an autistic person feeling overstimulated, uncomfortable, or even in physical pain.

- Sensory overload looks different for each person and intensity can vary depending on severity, context, and their typical response patterns.

- Proper support and accommodations make it possible to prevent sensory overload, or at least mitigate your triggers.

For autistic and neurodivergent adults, sensory overload can feel like it hits all at once. Imagine you’re in a crowded restaurant. At first, the talking all around you becomes intrusive, and you can’t concentrate on the person across from you, no matter how hard you try. Then, the repeated sound of clinking of glasses and forks on porcelain intensifies, grating at your nerves, and the smell of perfume on the woman next to you becomes unbearably strong.

Suddenly, you’re in full-body panic mode because this combination of sensory experiences is simply too much. Allistic people can compartmentalize and block out these types of input, but autistic people often cannot.

Sensory processing differences—formerly referred to as a “sensory processing disorder”—are the variations in how the brain receives, interprets, and responds to information gained through your senses from the environment and the body. Autistic people’s sensitivity to stimuli will vary depending on the individual.

Sensory overload, on the other hand, can happen when a neurodivergent person’s brain becomes so overwhelmed by sensory information in an environment (think: sights, sounds, smells, textures) that their body goes into a state of panic and fight or flight mode.

“Sensory overload, or strong sensory input, can often be described as ‘physically painful’ or ‘making my skin crawl’ by autistic adults,” says Jackie Shinall, PsyD, head of reliability and quality assurance at Prosper Health. “For example, they don’t necessarily feel anxious or stressed by the input, but rather uncomfortable overall, especially physically.”

While anyone can experience sensory issues and sensory overload, they are especially common among autistic adults and neurodivergent people more broadly. In fact, a 2021 study published in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders surveyed autistic adults and found that 93.9% reported being extra sensitive to sensory experiences. Autism and sensory overload often go hand-in-hand.

If you have questions about sensory overload in autistic adults, you’ve come to the right place. In this article, we'll cover what sensory overload is, why it happens, what it feels like, and how to prevent and recover from it.

What is sensory overload?

“Sensory overload” isn’t a clinical term, but rather a description of what happens when someone has become so overwhelmed and overstimulated due to taking in too much sensory information that they can no longer process additional stimuli. Sensory overload in autism typically goes hand in hand with hypersensitivity, a trait common in many autistic adults.

To be clear, sensory overload is a nervous-system safety response—absolutely not a behavioral issue, attention-seeking behavior, or an adult “having a tantrum”.

“Rather, it’s overload and distress of the nervous system,” Shinall says. “It could lead to behaviors that may look like a ‘meltdown,’ such as yelling, walking away, increased stimming behaviors, as well as shutting down, where they struggle to articulate their thoughts and feelings in the moment.” Again, these aren’t behavioral issues: they’re genuine differences in the nervous system’s ability to process information.

Sensory overload isn’t just about feeling anxious or stressed out—it can lead to a full-body shutdown. “It happens when multiple sensory inputs hit us all at once, like a crowded grocery store with bright lights, overlapping sounds, strong smells, and people bumping into you,” says Kory Andreas, an autistic psychotherapist in private practice specializing in therapy and diagnostic assessments for other autistic adults.

“When you’re already taxed, this kind of environment can push your nervous system into crisis mode. Some of us go flat, lose the ability to speak, or need to flee immediately.”

How sensory overload affects functioning

Sensory overload impacts functioning across all domains simultaneously because it's a whole-system neurological event, not an isolated experience. Here’s how it affects emotional, cognitive, and physical functioning, according to Shinall:

Emotional regulation

Autistic adults may be more likely to have larger reactions to smaller frustrations.

Sensory overload can lead to challenges regulating emotions and be perceived as “overreacting,” when in fact, they aren’t overreacting at all. “Rather, their nervous system is completely overwhelmed and cannot access the parts of their brain that help with emotional regulation,” Shinall says.

Cognitive functioning

When the brain is overwhelmed with sensory input that it can't filter or process, cognitive resources become compromised.

Many autistic people describe having significant challenges articulating and expressing their thoughts and feelings when they are experiencing sensory overload. Making decisions, answering questions, or attempting to plan may feel impossible.

Similarly, they can have challenges understanding spoken language, paying or maintaining attention, or accessing their memory when they are overwhelmed.

Physical functioning

Autistic adults often describe physical pain, such as in their ears with loud/specific sounds, or full-body discomfort in response to specific input. Other individuals may describe feeling like their “skin is crawling” or their nervous system is “buzzing.”

Some sensory input could also cause nausea, headaches, and body aches, among other physical symptoms. Often following an experience of sensory overload, autistic adults feel exhausted or fatigued and need time to recover.

A “meltdown” occurs when the nervous system is completely overwhelmed, and a person is no longer able to regulate their emotional and cognitive systems, which may also result in physical discomfort or pain. Meltdowns are an involuntary reaction that occurs in many autistic people when they experience sensory overload.

This can lead to feeling unable to cope and may lead to crying, screaming or yelling, hitting or throwing things, and sometimes even self-injurious behavior (e.g., hitting self in legs, squeezing body parts very tightly). “These are not behavioral problems, but a true reaction that is often outside of one’s control,” Shinall says. “Critically, meltdowns are not anger management issues or manipulation. They're a nervous system in overload.”

The reaction may be much less observable in some people who experience internalized shutdowns more often than full-blown meltdowns.

What causes sensory overload in autistic adults?

The causes of sensory overload are typically triggers related to a stimulating environment, including sights, sounds, textures, smells, and tastes. Autistic brains process sensory input differently: stimuli don’t “fade out” the way they do for neurotypical people.

“The autistic nervous system often processes sensory input with different intensity, speed, or filtering than neurotypical systems,” Shinall explains. “Differences in sensory processing for autistic adults can result in sensory overload, in which an individual’s capacity to filter and process incoming sensory information is overwhelmed by too much sensory input.”

Constant awareness of sensory input can lead to distress, exhaustion, and sensory fatigue. Sensory overload can build gradually or occur suddenly, depending on context, energy, and support. Similarly, sensory processing can vary within a person and fluctuate based on things like stress and their current environment.

The eight senses and their roles in sensory processing

While most of us are familiar with the five senses, there are actually eight sensory systems that can contribute to sensory overload:

- Sight: Provides information about distance, edges, boundaries, shapes, and colors.

- Sound: Provides information about volume, location, language, tone, pitch, rhythm, and sequences. A 2024 study found that noise had the greatest impact on whether someone experiences sensory overload.

- Smell: Provides information on scents and odors, including natural and artificial fragrances.

- Taste: Provides information on flavors.

- Touch: Provides information about types of touch, temperature, pain, and comfort.

- Vestibular: Provides information about movements backwards and forwards, and circular motion. It supports balance and movement.

- Proprioception: Provides information about where the body is positioned, where our body parts are (even when we can not see them), and how much force we are using through our muscles. It contributes to body awareness.

- Interoception: Provides information about sensations like feeling hungry, thirsty or full, needing the toilet, and experiencing hot and cold. It helps you pick up on internal clues.

Hypersensitivity, hyposensitivity, and sensory seeking

Every autistic adult has a unique sensory profile that describes how their nervous system responds to sensory input. “It maps patterns of sensory processing—what types of input are overwhelming, what's sought out, what goes unnoticed, and how these patterns affect daily functioning,” Shinall explains.

A thorough sensory profile examines all eight sensory systems. “For each system, it identifies whether the person is hypersensitive (over-responsive), hyposensitive (under-responsive), sensory-seeking, or some combination depending on context,” Shinall says.

Some autistic people with sensory processing differences have hypersensitivity, making them more sensitive to sensory experiences than others. On the other hand, others have hyposensitivity, meaning they’re less sensitive to sensory experiences than others.

For those with hyposensitivity, the lack of sensory input may be distressing or frustrating, so they may be sensory seeking and look for more intense sensory experiences in order to get more input. In contrast, those with hypersensitivity often engage in sensory avoidance.

According to a 2021 study that surveyed autistic adults, 93.4% identified as hypersensitive, while 28.6% identified as experiencing sensory hyposensitivity, and 41.4% indicated that they experienced sensory seeking.

Autistic people aren’t the only ones with sensory processing differences: they also affect people with ADHD, anxiety, PTSD, and other neurodivergences. But it’s important to keep in mind that having sensory differences alone doesn’t mean someone must be autistic—including among people who are neurodivergent.

What are common triggers for autistic adults?

Here are some common triggers for autistic adults in different environments and sensory overload examples, according to Andreas:

- Work/public spaces: Mouth noises, people chewing, microwave smells, chatter, people interrupting without warning, being perceived in public spaces, sounds like people squeezing plastic bottles, repetitive noises like tapping a pen, loud construction work, car horns, and motorcycles revving.

- Social: Forced small talk, unpredictable conversation shifts, sensory chaos at restaurants, grocery stores, or social events.

- Home: Temperature fluctuations, loud commercials, cooking smells, a barking dog, negative tactile experiences (like touching a microfiber cloth with dry hands), the sound of the vacuum, cleaning products with a strong scent.

- Digital: Unexpected notifications, loud pop-up ads, bright screens, flashing images.

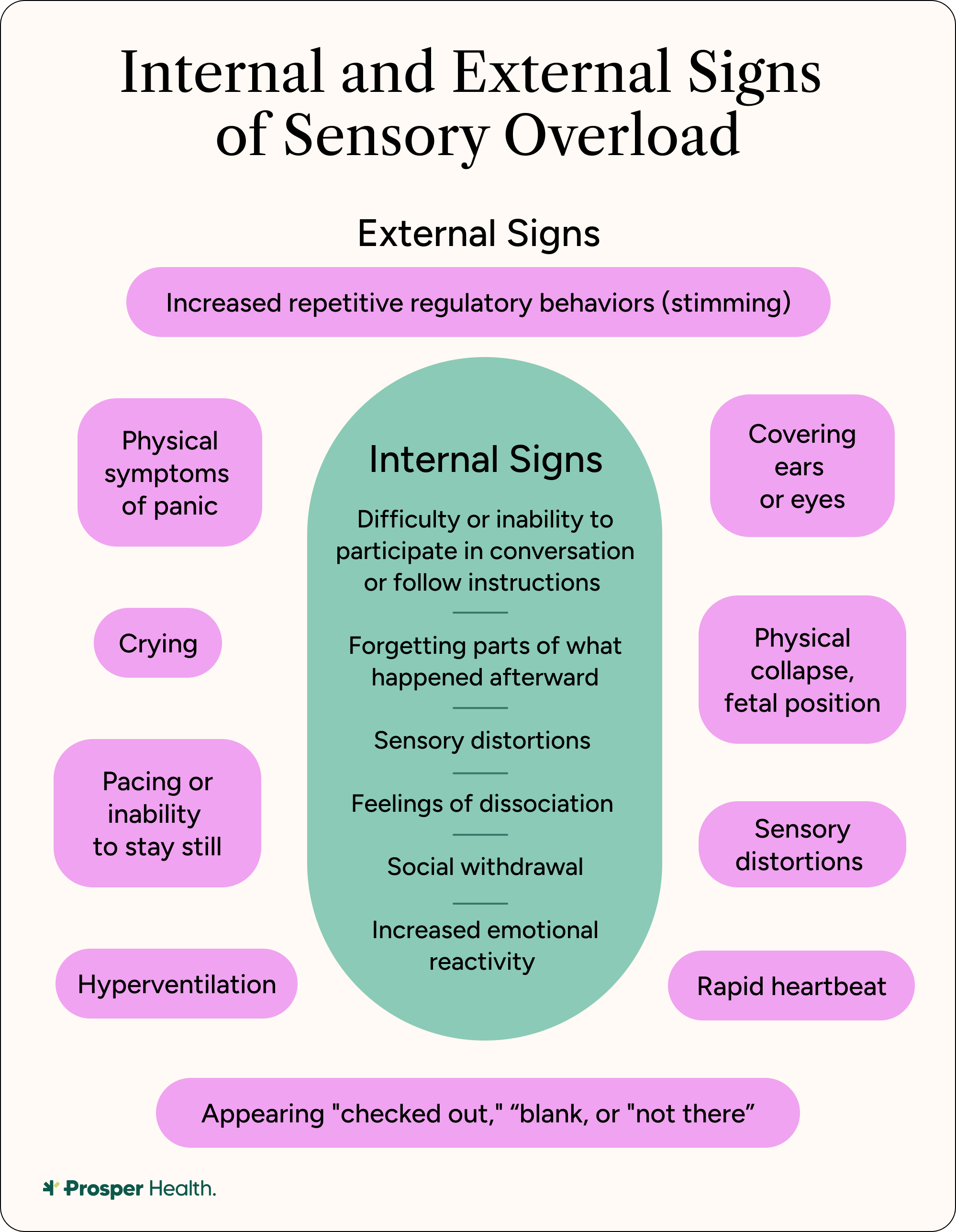

What does sensory overload look and feel like?

Sensory overload looks different for each person and can vary even within the same person. For example, while some respond with panic or shutdown, others feel exhausted. Regardless of how someone reacts to sensory overload, it’s important to approach them (or yourself) with compassion. Here are some of the common physical, emotional, and cognitive signs of sensory overload, according to Shinall:

Physical

- Increased stimming or repetitive movements (more intense rocking, hand-flapping, pacing, fidgeting)

- Physical tension (clenching jaw, tight shoulders, rigid posture)

- Sensory distortions (sounds becoming painful, lights seeming brighter, touch feeling unbearable)

- Covering ears or eyes

- Headache or feeling of pressure in the head

- Nausea or stomach discomfort

- Dizziness or disorientation

- Feeling overheated or flushed

- Trembling or shaking

- Rapid heartbeat

- Seeking escape routes or moving toward exits

- Screaming, yelling, or making loud vocalizations

- Hitting, throwing objects, or physical aggression (often not directed at people)

- Self-injurious behavior (hitting self, head-banging, scratching, biting)

- Pacing frantically or inability to stay still

- Hyperventilating or breathing difficulties

- Going very still or being unable to move

- Physical collapse (needing to sit or lie down)

- Covering face or head (with hands, hood, blanket)

- Turning away or curling into fetal position

- Appearing exhausted or falling asleep

Emotional

- Withdrawal from conversation or social interaction

- Shorter responses or becoming quieter

- Increased irritability or emotional reactivity to minor things

- Requesting to leave or expressing discomfort

- Crying uncontrollably or sobbing

- Verbal outbursts (swearing, saying hurtful things they don't mean)

- Appearing panicked or in extreme distress

Cognitive

- Difficulty following conversation or appearing distracted

- Inability to respond to verbal communication

- Inability to follow instructions or reasoning

- May not remember parts of what happened afterward

- Becoming completely nonverbal or having severely limited speech

- Appearing "blank," "checked out," or "not there

- Not making eye contact or tracking visually

- Not responding to questions or instructions

- May be aware of what's happening around them but unable to respond

- May experience significant dissociation where they're genuinely disconnected from their surroundings

- Feeling disconnected from body or surroundings

“To someone unfamiliar with sensory overload, meltdown might look like a tantrum, emotional outburst, or anger management issue,” Shinall explains. “Shutdown might look like defiance, rudeness, ignoring people, or being ‘dramatic.’ This misinterpretation is incredibly harmful because it leads to responses that worsen the situation—demanding the person ‘calm down,’ expecting them to explain themselves, or becoming frustrated with their lack of responsiveness.”

Lindsey, 39, experiences multiple types of sensory overload, but they all generally feel the same. “It feels like my whole body is rejecting whatever is happening,” she explains. “If it’s too much sound, lights, tastes, or otherwise—or a combo of them—my entire heart is telling me to make it stop, and my body is reacting accordingly.” Lindsey sweats and her heart and mind race. “I’m constantly thinking of any way to get out of the situation,” she says. ”I have to change clothes or spit out the food. I have to plug my ears or put in earplugs. I have to yell or hold myself to make the entire experience slow down, just enough to be tolerable.”

Most of the time, people have one of four reactions to the stress of autistic overload:

- Fight: Confronting or standing up to a threat.

- Flight: Escaping or removing yourself from a threat.

- Freeze: Becoming immobile or unable to take action when faced with a threat.

- Fawn: Trying to avoid conflict by pleasing others.

It’s important to note that these are involuntary nervous system reactions, not overreactions. “It’s not about bad behavior,” Andreas says. “Our bodies are reacting as though we’re in danger, because that’s how it feels. Our bodies process these triggers through the amygdala, and convince us we're dying, when others might not even notice these triggers.”

In addition to physical responses, like tensing up and becoming disoriented, Rose-Lauren, 32, who was diagnosed with AuDHD as an adult, panics when she experiences sensory overload, and tries to find her way out of the environment. “I’d find a way to go away, outside or to another room, where I can stand either close to a tree or a wall, or behind a door,” she says. “I would naturally seek out any space that had essentially no stimuli, and this would be done without telling anyone.”

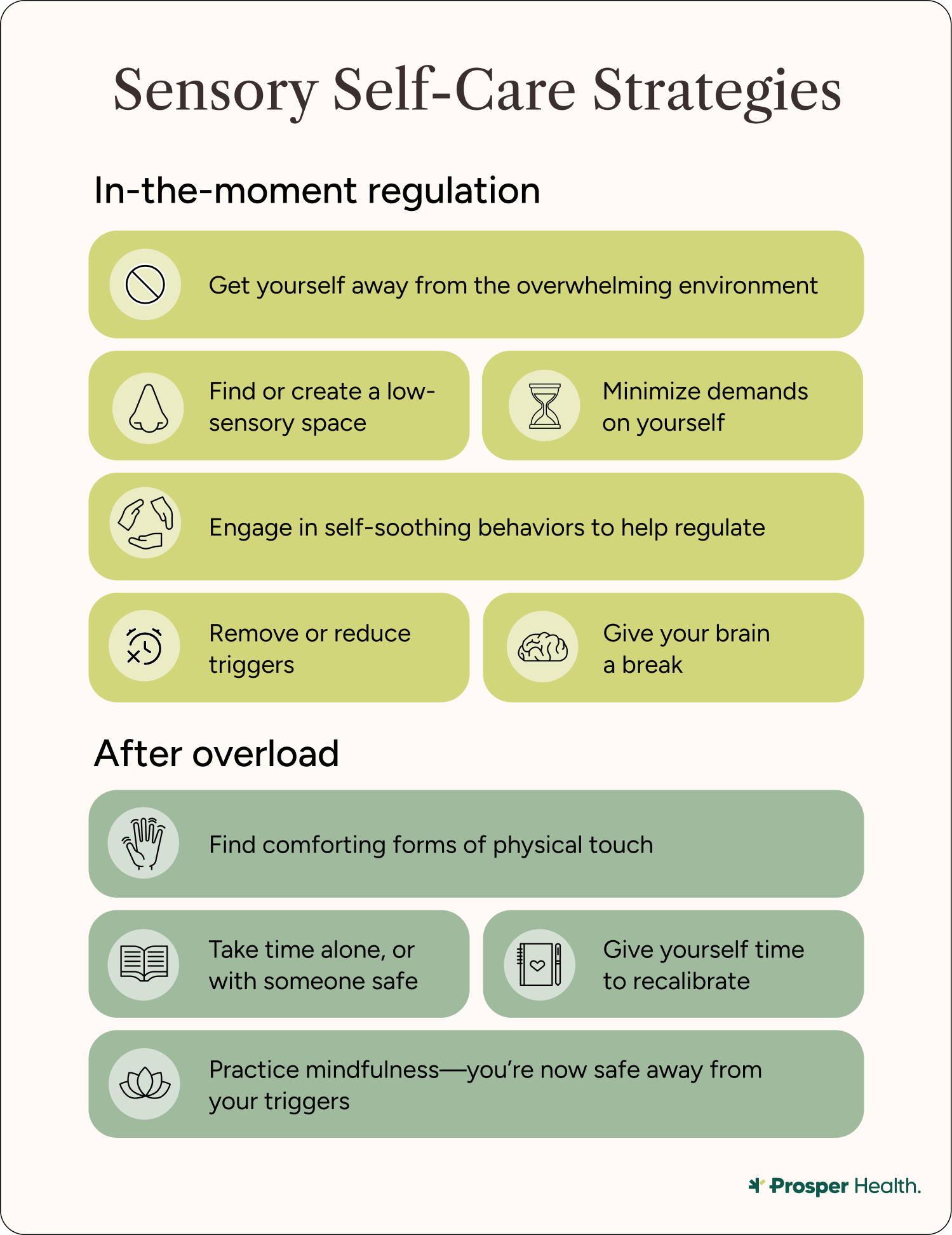

How to recover when you’re feeling overstimulated

Fortunately, there are ways to reduce sensory overload, including coping skills for overstimulation—although recovery will take different forms for different people. “Recovery requires tending to the nervous system,” Andreas says. Here are some tips for getting through sensory overload, both in the moment and after it has passed.

In-the-moment regulation

The priority is reducing sensory input as quickly as possible. Strategies include:

- Getting out: Leave the overwhelming environment as quickly as possible.

- Finding or creating a low-sensory space: Somewhere quiet and dim with minimal visual clutter.

- Removing or reducing triggers: Turn off lights, use noise-canceling headphones, remove uncomfortable clothing.

- Giving your brain a break: Minimize demands for communication, decision-making, or social interaction.

- Engaging in “stimming” behaviors to help regulate: This may look like rocking your torso back and forth, pacing, tapping, or using objects that help you feel calm (e.g., smooth rock, rubbing soft blanket, etc.)

- Use your sensory self-care kit: It can include items like sunglasses, noise-canceling headphones, fidget toys, and aromatherapy tools.

After overload

“Most autistic adults, following a meltdown or shut down, will need a period of recovery,” Shinall says. “This is also highly variable based on what the person needs.” Some examples include:

- Finding comforting forms of physical touch: This can be using a weighted blanket, hand pressure, or holding something textured.

- Recalibrating: Sit quietly alone in a dark room, or do whatever you need to do to reset.

- Being alone or with someone safe: Make sure you’re with someone you’re comfortable with at this time of vulnerability.

- Practicing mindfulness: Be present in the moment, now that you’re away from your triggers.

Rose-Lauren makes sure she practices self-care. “I cancel plans a lot,” she says. “I purposely live alone so that my home is my oasis and is completely packed out to match my needs. I have noise cancelling headphones, soft and fluffy blankets and hoodies, and a shower I can sit down in and just let the water fall over me.”

How to prevent sensory overload

In order to prevent sensory overload, it’s important to identify your own unique sensory profile, including personal patterns, triggers, and early warning signs.

“Preventing sensory overload requires a multi-layered approach that addresses environmental factors, personal management, and systemic accommodation,” Shinall explains. “The goal isn't eliminating all sensory input but creating conditions where the person's nervous system can function within its capacity.”

Some strategies could include:

- Bringing earplugs to a concert that will likely be loud

- Wearing sunglasses inside supermarkets and stores with extra-bright lights

- Wearing a face mask if you have to pass through somewhere with powerful scents

It’s not only about sensory avoidance; it’s also about being ready to mitigate circumstances beyond your control.

One way to stay on top of your triggers is to track environmental factors that may contribute or lead to sensory overload. This could be the time of day when it makes you feel overwhelmed, your mood, your energy level, and your social load. This is all about control and predictability: prevention is often about choice and pacing. Of course, there are some factors that make things harder, like a lack of control, low energy, poor mood, and a lack of environmental support.

Unfortunately, there will be times when sensory overload can’t be entirely prevented. “Despite being considered ‘high masking,’ to totally avoid overstimulation, I don’t think I could live my life,” Rose-Lauren says. “I work two jobs, I have bills to pay, I have health issues to handle. I want to enjoy life and be outside and be social, but all of these things come with a heightened risk of over-stimulation. I always joke to people, avoiding it [would mean] staying cocooned in my bed with my fluffy things, with the temperature set low and my cat being peaceful.”

Sensory overload and potential meltdowns can be scary painful experiences, but remember that you (or your autistic loved one) will get through them.

Build a sensory self-care plan

While it’s impossible to control every circumstance you might find yourself in, it’s very possible to be prepared.

Regulating your nervous system means finding a balance between being overstimulated and understimulated, and the sensory environment plays an important role. For example, when overstimulated, you might choose calming sensory input like the deep pressure input of a tight squeeze, a weighted blanket, or rhythmic input such as rocking. These tools can bring the nervous system back into a calmer state.

Conversely, more intense sensory input, such as bouncing on a fitness ball or listening to music, can have stimulating qualities when understimulated. Each person’s sensory needs are different, and regulating your nervous system is a dynamic process requiring a personalized approach that can be developed alongside therapeutic techniques.

Create a sensory self-care kit

In the spirit of preparation and prevention, it can be helpful to build your own self-care kit containing some of the following items:

- Ear plugs or noise-cancelling headphones

- Weighted blankets

- Weighted eye masks

- Stretchy or textured fabric

- Star projectors

- Chewelry

- Fidget toys

- Calming scents

- Mints or something else that can mask bad tastes or textures

What works for autistic people experiencing sensory overload will vary, but these are all good starting point tools to try.

The idea behind the self-care kit is proactive regulation, rather than reacting after sensory overload happens. It can also be helpful to collaborate with therapists or the autistic community for other ideas of items to put in your kit.

Try a therapeutic approach

Some therapeutic approaches, such as mindfulness, body scans, and occupational therapy, can be useful in managing sensory processing differences. Occupational therapy treatment for sensory processing is called sensory integration therapy, which might include engaging in sensory activities or developing a sensory diet—a personalized plan of activities and actions that provide supportive sensory input.

Occupational therapy can also provide autistic adults with accommodation suggestions and teach them about their nervous system. Additionally, techniques like body scans can help you notice your body’s reaction to your sensory environment, allowing you to identify early signs of overstimulation. This will be more complex for those with hyposensitivity to interoceptive input, but it is possible to improve by practicing noticing sensations.

While sensory processing differences won’t go away, these therapeutic approaches can empower autistic adults to understand and manage sensory experiences when they are integrated into daily routines.

Find community support

Discussing sensory challenges with others who understand can provide both emotional support and some great practical recommendations.

You can find autistic communities, for example, through the forums on Reddit, Facebook groups, Prosper’s client community on Discord, or through peer autistic self-advocacy groups. Discussing sensory overload in autistic spaces can help combat the shame that so many adults face around their sensory overload, especially if meltdowns or shutdowns accompany it. In fact, emotional validation comes from shared experience.

Supportive individuals and communities can make a big difference in the life of someone with sensory processing differences by providing emotional and sensory support and fostering sensory-friendly environments.

Create sensory-friendly environments

Creating sensory-friendly accommodations is not just the responsibility of the autistic person––it’s a shared responsibility. Resources like the Job Accommodation Network (JAN) can help you start the conversation about workplace accommodations. Just as ramps are installed for wheelchair users, adjustments can be made to create more accessible spaces for those with sensory processing disorders.

For those looking to create sensory-friendly environments, consider noise control, adjustable lighting, comfortable textures, limiting aromas and providing quiet areas. These sensory accommodations are crucial in work and public spaces where sensory overload is more difficult to manage.

Respecting your sensory profile

Sensory needs are safety needs for the nervous system, not preferences nor quirks. And sensory overload is a complex and difficult experience that involves the body’s response to danger. While the reaction to sensory overload can look and feel physical, cognitive or emotional, the cause is rooted in the body’s response to excessive sensory information. It’s important to view sensory regulation as self-knowledge, not avoidance.

There are a number of personal and external approaches to coping with sensory overload, and the best approach is prevention. Ideally, there would be more inclusive environments that honor sensory diversity.

By understanding and respecting your sensory profile and trusting yourself, you can enhance your quality of life, and together we can create more accessible environments for autistic people with sensory processing differences.

How Prosper Health can help

Are you an autistic adult who struggles with sensory overload? Or, are you seeking a formal autism diagnosis so you can receive accommodations for your sensory needs? Prosper Health can help.

Neurodivergent-affirming clinicians, like the ones at Prosper Health, approach sensory regulation as a collaborative process where the autistic person is the expert on their own sensory experience. The clinician's role is providing framework, language, validation, and support.

Should you choose to seek therapeutic support through Prosper Health you’ll also gain access to a community of autistic adults sharing their experience and sensory overload management tips.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is sensory overload?

Sensory overload can happen when your brain becomes overwhelmed by sensory information—like sights, sounds, and smells—in an environment.

What does overstimulation feel like?

Overstimulation doesn’t feel the same for everyone, although most people experience some physical, emotional, and cognitive effects of sensory overload. Physically, it might involve tensing muscles, stimming, and physical symptoms of panic. Emotionally, it might involve increased emotional reactivity to minor things, crying uncontrollably, or verbal outbursts. Cognitively, it might involve difficulty following conversation, distractibility, inability to respond to verbal communication, or feeling disconnected from your body and surroundings.

How can sensory overload be managed?

In order to manage and prevent sensory overload, it’s important to identify your own unique sensory profile, including personal patterns, triggers, and early warning signs.

For example, bring ear plugs to a concert that will likely be loud. Wear sunglasses inside supermarkets and stores with extra-bright lights. Wear a face mask if you have to pass through somewhere with powerful scents. It’s not only about sensory avoidance; it’s also about being ready to mitigate circumstances beyond your control.

Another way to stay on top of your triggers is to track environmental factors that may contribute or lead to sensory overload. This may include the time of day when it makes you feel overwhelmed, your mood, your energy level, and your social load.

Is sensory overload ADHD or autism?

Sensory overload is common among neurodivergent people, including those with ADHD and autism.

Sources

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9213348/

- https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/aut.2020.0074

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13803395.2025.2458539

- https://parent-send-support.essex.gov.uk/advice-send/understand-and-support-your-childs-needs/sensory-needs/eight-senses

- https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/about-autism/sensory-processing#What%20is%20sensory%20overload?

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0891422220301268

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-psychiatry/article/abs/atypical-sensory-profiles-as-core-features-of-adult-adhd-irrespective-of-autistic-symptoms/B64037075E93613CF99CCF271F328DB8

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0164212X.2022.2131695

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/10870547251361226

Related Posts

.png)

What Is Stimming? A Guide to Autistic Self-Regulation and Expression

Self-stimulatory behavior, or "stimming", is a physical behavior used by autistic and other individuals (including those who are allistic) to regulate emotional or sensory stress, sensory seek, and/or express their emotions. In autistic people, stimming is often repetitive and is a way to calm their minds and bodies.

Personally, I have stimmed my entire life in many ways. Notably, I am always carrying a rolling stim toy with me. It helps to ground me when I get anxious, or when the noises in a room are too loud or overwhelming.

Everyone stims, whether they realize it or not. If you’ve ever bounced your knee while bored, or clicked a pen open and closed, you’ve stimmed. But for autistic folks, stimming serves a key role in sensory and emotional management. It’s not something to fix, but rather something to understand.

In this article, we’ll explain what stimming is, why it happens, and how to support yourself or someone around you who stims.

Meltdowns in Autistic Adults: Why They Happen, What They’re Like, and How to Live with Them

When many people hear the word “meltdown,” they might envision a kicking-and-screaming child, lashing out because their parent or caregiver said “no.”

While that is an accurate description of a typical child meltdown, a meltdown in an autistic adult is entirely different, and not to be confused. In fact, in many cases, meltdowns in autistic adults can look like the antithesis of a childhood tantrum. Instead of engaging in "why won't you give me what I want!?" goal-oriented behaviors that are synonymous with tantrums, autistic adults usually need to get away from people and into a calm, dark, safe space during a meltdown.

The most important thing to remember about an autistic meltdown is that it’s not a choice, but an involuntary nervous-system response to intense overload or stress. If someone is experiencing a meltdown, they are not intentionally acting out: They are dealing with complex emotions just like the rest of us, and don’t deserve the ongoing stigma that is attached to autism—and by extension, meltdowns.

Victoria Mindiola (they/theirs/she) is an autistic person who works as an inclusion consultant and educator, focusing on advocacy for neurodivergent students. When Mindiola experiences an autistic meltdown, they say they frantically need “to find a place that is safe and dark and quiet and empty of people.”

Unfortunately, the stigma around autism and meltdowns remains because adult-focused research and resources are still lacking. While there’s plenty of research available on autistic meltdowns in children, there is limited data from the perspective of autistic adults.

In this article, we’ll provide a comprehensive breakdown of autistic meltdowns in adults: What they are, why they happen, how to identify early signs, and how to support yourself or someone else.

Masking Autism: What It Is and Why It’s Exhausting

Imagine you’re hanging out with a group of friends. On the outside, this scenario looks like a typical get-together: Everyone is laughing, making eye contact, and visibly comfortable with one another.

But for some people, there is a very good chance that much of their behavior is the result of masking, or a concealment of their autistic traits. Sure, these people may come off socially at ease, but a debilitating dance is taking place behind their eyes.

“After I've been hanging out with people, I need to take a nap for one to two hours…my brain literally needs to shut off. I feel like a computer that needs to reboot,” says Aura Marquez, an author living with autism.

Marquez says she’s been masking since she was in late elementary school: “It’s gotten to the point where I can’t turn it off.”

Masking autism is how many neurodivergent people navigate a neurotypical world, so it’s important to understand the reasons behind this practice in order to minimize stigma. While masking may provide some benefits, it’s important to also remember the toll this behavior takes on one’s mental health.

That why learning how to also unmask, under the right conditions, is essential to helping autistic people feel comfortable in their own skin. This article will explore options for those who wish to stop masking, as well as support for those who do mask.

.webp)