Key Takeaways

- Autistic adults often experience chronic nervous system dysregulation, which is increasingly being linked to masking.

- In addition to the five senses, lesser-known sensory systems (proprioception, interoception, and vestibular) play a role in helping autistic individuals regulate their nervous systems.

- Mindfulness, yoga, and other somatic practices can help bring the nervous system to a more regulated state. Stimming can also be calming and regulating.

- Therapeutic approaches like occupational therapy and somatic therapy can help.

- Self-awareness about sensory preferences and signs of dysregulation are the first steps in building a toolkit to combat an unbalanced nervous system.

For me, nervous system dysregulation begins at the center of my body: a quaking, liquid feeling that leaves me unsettled. I have episodes of verbal shutdown, and may engage more in stimming: rocking back and forth, humming to myself, and bouts of anger that have no outlet. It’s in times like these that I try and re-center myself through deep breathing, reducing sensory input, and leaning on my support systems.

Autistic people often experience heightened nervous system responses, which can lead to dysregulation, especially in overwhelming environments. This can lead to chronic stress, shutdowns, meltdowns, and sensory overwhelm. Addressing dysregulation can improve quality of life, positively impacting physical health, emotional regulation, sensory processing, and mental health over all.

In this article, we’ll discuss tools to help autistic adults shift out of dysregulation and offer strategy suggestions to become more regulated and maintain equilibrium. However, as always, it’s best to consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new therapeutic techniques.

What is nervous system regulation?

Your nervous system is made out of nerve cells and acts as a network of connections that carries messages between your brain and the rest of your body. There are two main parts of the nervous system: your central nervous system (CNS) and your peripheral nervous system (PNS).

Your CNS includes all the nerves in the brain and spinal cord, whereas the PNS controls anything outside of the skull and spine, like your organs, muscles, and skin. When these two systems are balanced, it's easy to feel calm and unstressed.

Béa Victoria Albina, NP, MPH, SEP, host of The Feminist Wellness Podcast, explains, “Nervous system regulation is the ongoing dance between your body, your environment, and your ability to track your own signals.”

Albina continues, “If you imagine the nervous system like an animal in the wild, regulation is the way that animal stays attuned to the land beneath it, adjusting posture, breath, pace, and awareness so it can keep living, relating, and responding to the world without burning itself out.”

Understanding the autonomic nervous system

Part of your peripheral nervous system is your autonomic nervous system (ANS), which regulates automatic bodily functions like heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, digestion, pupil dilation, sweating, and other involuntary functions. The ANS is split into three parts:

- Sympathetic nervous system (SNS): Often referred to as the fight, flight or freeze system, it prepares the body for a stress response by increasing heart rate, opening airways and pausing digestion.

- Parasympathetic nervous system (PNS): Otherwise known as the rest-and-digest system, it conserves energy by slowing down the heart rate, stimulating digestion and promoting relaxation.

- Enteric nervous system (ENS): This is often referred to as the second brain. It’s the network of neurons in the walls of the gastrointestinal system that regulates digestive processes like gut motility.

“The autonomic nervous system is constantly measuring threat, support, predictability, sensory load, and internal resources,” Albina adds.

The SNS and PNS reciprocally balance each other: when one ramps up, the other compensates. However, when they’re out of balance for a long period, nervous system dysregulation occurs.

A common example is a panic attack, where the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) triggers intense physical symptoms, like a racing heart, shortness of breath, dizziness and a sense of impending doom—even when there's no actual threat.

This imbalance occurs between the body's fight-or-flight response and its rest-and-digest state, both of which are controlled by the ANS. As one system ramps up, the other naturally slows down, but when they fail to balance, dysregulation can occur.

When these systems are dysregulated in autistic people, it can show up as both overactivation (hyperarousal) and underactivation (hypoarousal).

Those with autism also have a high rate of co-occurring conditions like depression and anxiety disorder, which may also impact nervous system function. Some other co-occurring conditions that may modulate the nervous system are:

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): Rapid heartbeat upon standing

- Orthostatic hypertension: Drop in blood pressure upon standing

- Thermoregulatory dysfunction: Difficulty in body temperature regulation

- Enteric dysautonomia: Abnormal gut motility

Vagal tone and the "window of tolerance"

It’s also important to consider the effects of the vagus nerve on stress. The vagus nerve is the longest nerve in the body, and it regulates everything from the heart to the gastrointestinal system. High vagal tone is associated with a better ability to recover from stress because it is better able to activate the PNS, or the rest-and-digest system. High vagal tone means a body can manage stress responses better, because your PNS is linked to the ability to slow your heart rate.

On the other hand, low vagal tone is linked to a heightened stress response—leaving the SNS activated for longer. With low vagal tone, an individual may be stuck in a high stress response.

Low vagal tone can contribute to a narrower "window of tolerance"—the range in which someone can manage stress and stay regulated.

Kaila Hattis, MA, LFMT, owner of Pacific Coast Therapy, explains, “The window of tolerance refers to the space in which an individual is able to be present without feeling overwhelmed or shutting down.”

For autistic individuals, she adds, the window of tolerance, which can already be narrower than for neurotypical peers, can narrow further during times of high sensory input, times of transition, and periods of unpredictability.

“Even slight increases in a person's window of tolerance have provided a smoothness to daily functioning and give individuals more control over situations that would previously cause them to shut down,” she says.

If an autistic individual has low vagal tone, that window of tolerance can pass more quickly, leading to shutdowns and sensory overwhelm.

What are signs of a dysregulated nervous system?

Studies demonstrate that autistic individuals tend to have a higher activation of the sympathetic nervous system (fight, flight, or freeze) and lower activation of the parasympathetic nervous system (rest-and-digest). Autistic individuals may experience a higher than average resting heart rate, breathing rate, and pupil size, and may struggle with restful sleep.

Hyperarousal: This is when the sympathetic fight-or-flight response is activated. It means that coming back to a level of calm can be more difficult for autistic individuals.

Hypoarousal: This is when the body enters a state of shutdown or dorsal vagal response, leading to dissociation, low energy, and numbness.

For me, nervous system dysregulation is uncomfortable and recognizable: shaking hands, sweating, and heightened heart rate are all clues that tell me I’m operating outside of normal function and need to try and regulate. Some other common signs of nervous system dysregulation are:

- lightheadedness/fainting

- Rapid heart rate

- Digestive problems (i.e. nausea, constipation, indigestion)

- Fatigue

- Brain fog

- Sweating

Occasionally, if I've been in a state of hyperarousal for too long, I can plunge into hypoarousal and full shutdown.

Hattis confirms that she sees both in her patients with dysregulated nervous systems.

“The amount of sensory input increases dramatically in hyperarousal. Racing thoughts occur, and many of my clients report that they want to leave the space in which they are located. On the other hand, hyperarousal is the exact opposite, where energy decreases and an individual feels disconnected or numb.”

Albina adds that in her practice, she sees both responses—and that they often show up in the sensory system first: sounds feel sharper, lights harsher, textures unbearable.

“Some folks describe it as ‘my skin being too thin for the room’ or ‘my brain turning into static,” she says.

.png)

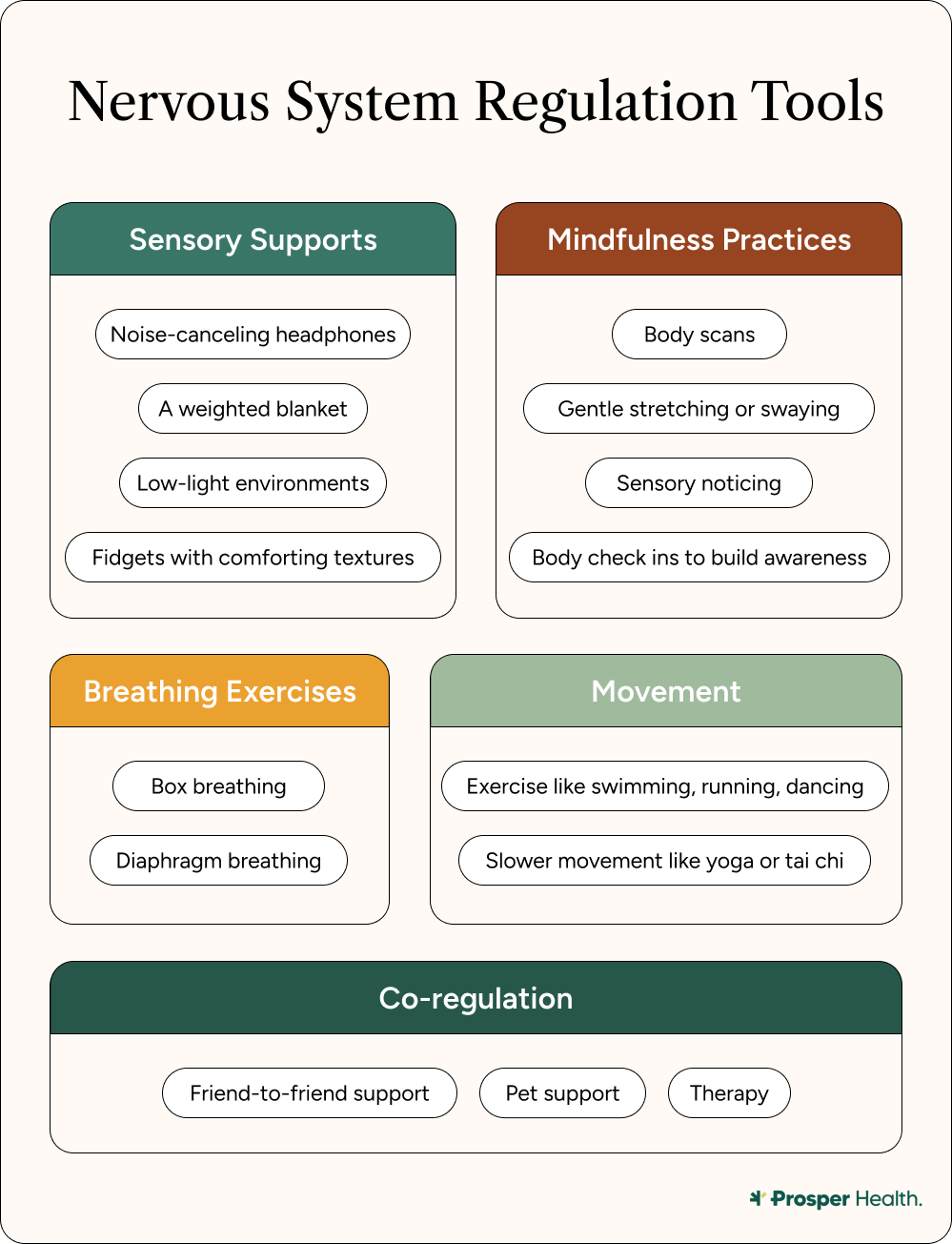

How autistic adults can regulate their nervous systems

Having a calm, regulated nervous system has a positive impact on mental and physical health. Personally, I struggle with regulating my own nervous system, and because of that have had to come up with multiple strategies to find balance. It’s important to remember, too, that regulation isn’t control, but rather safety—allowing autistic individuals to process challenging sensory environments and overwhelm while modulating their nervous system.

Here are some strategies and regulation tools for calming a dysregulated nervous system.

Sensory-based regulation tools

- Stimming: Short for self-stimulatory behavior, stimming, which is the repetitive use of movement, sounds, or objects, is a common way for autistic adults to regulate their nervous systems. Stimming helps to down-regulate the nervous system, providing a calming, self-therapeutic effect. Stims can be body-based (i.e. rocking) or may utilize tools (i.e. stim toys). Stimming helps regulate the nervous system, providing either calming or alerting effects depending on what's needed.

- Proprioceptive input: Proprioception, or the perception of where a body is in space, can offer a sense of pressure and grounding, which improves body awareness. Some examples of proprioceptive input are pushing or pulling heavy objects (heavy work), jumping, climbing, using a weighted blanket, squeezing a stress ball, and practicing yoga.

- Vestibular input: The vestibular system indicates spatial orientation and balance in a body, and vestibular input can be used to calm or stimulate. While this technique should be personalized to the individual because of its varied responses, it can help with attention, spatial awareness, and balancing emotions. Some examples are: swinging, rocking, spinning or rolling, balance activities. Vestibular input can fall under the umbrella of stimming, or be a separate coping mechanism.

- Interoceptive input: Interoceptive awareness supports self-regulation through the identification of internal states like anxiety, fatigue, or the need for movement. This can look like developing mindfulness practices that focus on bodily sensation, emotion check-ins using body maps, breathing exercises, and intentional breaks to check in with bodily states. However, it’s important to know that these internally-focused mindfulness activities can be activating for those with chronic pain—so tread carefully.

Mindfulness practices

When dealing with my own dysregulated nervous system, I engage in a number of mindfulness practices, which are a set of actions that allow someone to feel safe, supported, and anchored mentally and physically. Research indicates that mindfulness practices can positively impact psychological distress.

The following are part of mindfulness practices:

- Body scans: Body scanning involves focusing on different parts of the body to identify sensations. Sensations can look different for everyone, but many experience focusing on sensations as a buzzing or warming, but any difference noticed is okay. The key is to isolate each part of the body and identify the value of the sensation.

- Mindful movement: This practice focuses on movement to release stress, with an emphasis on sensation. Yoga is a classic example of a mindful movement, as is tai chi, meditative walking, and even gardening. The key is to use the body to notice how the body feels.

- Observational practice: This practice relies on identifying thoughts and emotions without trying to change them. Nonjudgmental observations can help an individual identify exactly how they are feeling both physically and mentally, so they can move past any challenges.

- Sensory engagement: Engaging with a sensory environment can be a good first step in noticing a system in hypoarousal, because it asks the individual for external observation rather than internal. Focus here is on sounds, textures, and smells, and calling awareness to each of them in turn.

Mindfulness practices can be incorporated into daily chores, such as washing the dishes, or taking the dog on a walk. I pair my mindfulness practice with playing cello, which allows me to deepen my understanding of my stress levels while releasing judgment of my anxieties. It’s worth noting that being quiet or still is not a requirement; the only requirement is the reflective behavior of asking yourself how an experience makes you feel.

Breathwork exercises

Breathing exercises activate the parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) nervous system, and positively impact vagal tone. Slow, intentional breathing signals to the brain and body that it is safe to relax. Here are some breathing exercises that are clinically indicated to reduce stress.

Diaphragmatic breathing

Also known as belly-breathing, diaphragmatic breathing encourages full oxygen exchange, and can slow the heartbeat and stabilize blood pressure. Here’s how to do it:

- Lie on your back with your knees bent.

- Place one hand on your upper chest, and the other on your belly below your rib cage

- Breathe in slowly through your nose, letting the air in deeply, toward your lower belly. Your upper hand should remain still.

- Tighten your abdominal muscles and let them fall down as you exhale through pursed lips. The hand on your belly should move down to its original position.

This can be practiced for 5-10 minutes a day, several times a day.

Box breathing

Box breathing is a kind of paced slow breathing with equal counts of four (like the equal sides of a box). Here’s how to do it:

- Breathe in slowly to the count of four.

- Hold in for a count of four.

- Breathe out to the count of four.

- After breathing out, hold your breath for another count of four.

This can be repeated for as many repetitions as necessary.

Alternate nostril breathing

Alternate nostril breathing is based on yogic breathing practices, and research shows that trying this practice for 30 minutes a day can lower stress levels. Here’s how to do it:

- Using your right thumb, close your right nostril.

- Take a slow breath through your left nostril

- Close your left nostril with your right ring finger while releasing your thumb from your right nostril. Breathe out slowly through your right nostril.

- Keeping your left nostril closed, breathe in through your right nostril. Close it again.

- Open your left nostril and breathe out through it.

Movement and exercise

Moving mindfully, or practicing exercise, improves the state of mind of adults with autism. While there are some stereotyped kinds of autistic movements like repetitive behaviors, moving freely, such as by dancing or running, are also helpful in returning the nervous system to a regulated state. Some other examples are swimming, playing sports, and lifting weights.

Co-regulation and connection

Co-regulation is defined as responsive interactions that provide support, coaching, and modeling, which can eventually lead to self-regulation. While we often think of co-regulation and connection as existing between two people, it can also exist between a person and their pet.

For example, I have a cat who supplies me with a lot of emotional support; when I’m feeling overwhelmed, she and I often seek each other out. Therapists can also be part of a co-regulation equation, providing warm support.

However, some might find connection draining rather than regulating, and both are valid. Remember, seeking support during nervous system dysregulation is individual.

Therapeutic techniques for nervous system regulation

There are many techniques for nervous system regulation, including different kinds of therapies. Some include:

Somatic therapy

Somatic-based therapies focus on bodily awareness and the mind-body connection. It helps to recognize internal cues, and reduce stored stress through breathing exercises, meditation, and other forms of movement like yoga. Though the data are limited on somatic therapy and autism, one survey associates it with improvements in anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Occupational therapy (OT) with sensory integration

OT focuses on developing strategies to regulate sensory input, sometimes including weighted items or blankets, movement, sensory diets, and other environmental adaptations. Therapy often starts in a clinic and moves outward to a client’s life. Although there is not much research into the effectiveness of OT for adults with autism, a survey indicates a growing body of interest in the matter, and anecdotal claims about its efficacy in reducing stress.

Polyvagal-informed therapies

Polyvagal therapies focus on vagus nerve regulation using rhythmic breathing, sound vocalizations, humming, and co-regulation tools. This is a developing therapeutic technique, and there is not yet a strong evidence base for its effectiveness, though theories have been promulgated for its clinical use.

Mindfulness-based therapies

MBT practitioners utilize many mindfulness practices, but in a clinical setting. The goal is to shift attention inward without judgment, slowing down racing thoughts and other physical reactions to stress. Studies have demonstrated a significant reduction in depression, anxiety, and rumination among adults on the autism spectrum.

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)

DBT focuses on emotional regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness, some with the incorporation of body-centered coping strategies. While DBT has been used among the allistic population with effectiveness for years, research is ongoing concerning how to best implement it among autistic adults.

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing

EMDR is a trauma-focused therapy that focuses on processing and releasing distressing memories at the root of chronic nervous system regulation. While EMDR has been used effectively for allistic populations with cPTSD, PTSD, and other forms of trauma, modifications to treatment are still being researched for autistic individuals.

How to build your personalized regulation toolkit

Even though nervous system dysregulation can happen unexpectedly, you can prepare for the next time you start to feel uncomfortable.

“A well-suited toolkit begins by looking at an individual's sensory patterns rather than listing off generic lists of tools. I have my clients test tools while they are doing their day-to-day activities and keep a record of which tools were able to affect their level of arousal in just a few minutes,” Hattis says.

Here are some ways to build your toolkit.

Step 1: Map out your states

The below is an example of how you might choose to map your different states of regulation and dysregulation. It’s important to know that individual experiences vary, so it’s important to consult with a therapist or practitioner to accurately judge how best to help.

Some questions to ask yourself while mapping out your states:

- What does being ‘revved up’ or in hyperarousal feel like?

- What does being ‘shut down’ or in hypoarousal feel like?

- What are my physical and mental cues that I’m balanced?

Step 2: Choose tools for each state

It’s helpful to prepare a go-to list of tools that help you in each state, based on your sensory preferences, access needs, and anything that feels safe or grounding. The below are options, but choose what feels best for your sensory profile.

Hyperarousal tools

- Mindful movement (rocking, dancing, swimming)

- Somatic exercises (deep breathing, humming)

- Body scanning

Hypoarousal tools

- Using a stim toy

- Co-regulation with a friend, therapist, or pet

- Observational practices

Regulation tools

- Daily mindfulness and movement practices

- Box breathing

- Observational practices to identify emotions

In the moment of hyper or hypoarousal, it can be hard to remember these tools to bring you back to balance. Here are some suggestions so you can find them easily:

- Create a note file on your phone

- Write down your toolkit in a journal

- Create a sticky note for your computer desk

- Send your ideas to a friend so you have support

- Communicate your choices to a therapist or practitioner

Step three: Use your toolkit, reflect, and adjust

After using your toolkit, it’s important to reflect on what went right and helped in the moment. As you try strategies, take notice: did your breathing slow? Did you feel more present? Or, alternately, did you feel yourself reengaging and emerging from fatigue? Experimentation is key when building a toolkit, because brains are dynamic—one size doesn’t fit all, and often things that may once have worked can change.

“Most importantly, the toolkit is most effective when someone understands what early signs of a specific emotional state indicate and which tools will best support that emotional state. When the right tool is used at the right time, it supports the individual's ability to maintain daily stability,” Hattis confirms.

Remember, it’s not about fixing yourself, but rather listening to your body’s cues. Albina agrees.

“A toolkit grows from curiosity, not pressure. The best tool is the one that works for your body, not the one wellness culture tells you should work,” she explains.

When to seek professional support

Sometimes, having a toolkit for regulating your nervous system might not be enough. Hattis explains that sometimes, long-time shutdowns or other patterns can indicate professional support is needed.

“This can be identified by long-term shut down of systems such as an inability to complete daily activities, irritability that seems abnormal for the individual, or a sense of separation from others as well,” she adds.

If you see a pattern of behavior—in either hypo- or hyper-arousal—that doesn't seem to changed no matter what tools you use, that’s another good indicator that having a professional weigh in could help.

It’s even better when practitioners are neurodiversity-affirming. Prosper Health, for example, employs clinicians who are both neurodiverse and trained to help neurodiverse clients navigate dysregulated nervous systems, ultimately redeveloping their toolkits.

Albina wants to make something clear, however: learning to trust your body’s signals again can feel like coming home to autistic individuals—even if that means consulting a professional for help along the way.

“Autistic bodies are not problems to fix. They are brilliant systems that respond honestly to their environment. Regulation is never about forcing a body to be quieter or more manageable. It’s about helping the body feel supported enough to do what it already knows how to do,” she says.

The bottom line

As an autistic person, I’m often trying to find a place of balance for my nervous system, and it’s no wonder. Folks with autism have a higher likelihood of developing a dysregulated nervous system because of increased sensitivity to sensory input; it’s simply part of our unique brains. Because of that, it’s important to learn signs of dysregulation, and how to develop a toolkit to come back to nervous system equilibrium. It’s also good to know when to seek professional support.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do you fix a dysregulated nervous system? First, you should identify if you’re in a state of hyperarousal (fight or flight) or hypoarousal (freeze). Based on that, employ strategies to help come back to equilibrium, like deep breathing, body scanning, or using a stim toy. If you find you’re stuck in a pattern of dysregulation, it’s important to contact a professional.

How does autism affect the nervous system? Autistic people often are more sensitive to sensory input, and therefore their nervous system can be sensitized to input more quickly. Autistic people may sensory seek by stimming as they become overwhelmed; over time, constant sensory input and dysregulation can lead to shutdown and burnout.

Can autistic adults regulate their nervous systems naturally? Yes! Autistic adults can learn techniques in the short term (coping) and in the long term (with a toolkit) to manage dysregulation.

What does an overstimulated nervous system feel like? An overstimulated nervous system may feel panicky, with a racing heart and non stop thoughts (hyperarousal) or fatigued, foggy, and dissociative (hypoarousal). In either case, the person experiencing overstimulation can employ strategies to come back to their window of tolerance (nervous system equilibrium).

Sources

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279390/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537171/

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/nmo.12817

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/aur.3068

https://autism.org/webinars/how-the-autonomic-nervous-system-may-govern-anxiety-in-autism/?referrer_domain=docs.google.com&fbp=fb.1.1763993876014.532283232394473961

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7449076/

https://aane.org/autism-info-faqs/library/restoring-the-autistic-nervous-system-a-gentle-path-to-regulation/

https://autism.org/webinars/how-the-autonomic-nervous-system-may-govern-anxiety-in-autism/?referrer_domain=docs.google.com&fbp=fb.1.1763993876014.532283232394473961

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6728747/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11506216/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10741869/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5769199/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11575101/

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0124344#sec035

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10162488/#bib16

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12302812/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22964266/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38435330/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9806468/

Related Posts

.png)

What Is Stimming? A Guide to Autistic Self-Regulation and Expression

Self-stimulatory behavior, or "stimming", is a physical behavior used by autistic and other individuals (including those who are allistic) to regulate emotional or sensory stress, sensory seek, and/or express their emotions. In autistic people, stimming is often repetitive and is a way to calm their minds and bodies.

Personally, I have stimmed my entire life in many ways. Notably, I am always carrying a rolling stim toy with me. It helps to ground me when I get anxious, or when the noises in a room are too loud or overwhelming.

Everyone stims, whether they realize it or not. If you’ve ever bounced your knee while bored, or clicked a pen open and closed, you’ve stimmed. But for autistic folks, stimming serves a key role in sensory and emotional management. It’s not something to fix, but rather something to understand.

In this article, we’ll explain what stimming is, why it happens, and how to support yourself or someone around you who stims.

How to Deal with Sensory Overload in Autistic Adults: Effective Strategies and Solutions

Sensory overload is a common challenge for autistic adults. Bright lights and unexpected sounds may seem harmless to some, but to the autistic brain, they can trigger the same physiological responses that bodies enter when facing something dangerous. This is why so many individuals on the autism spectrum find sensory-heavy environments so overwhelming.

A large proportion of autistic adults report experiencing sensory challenges, sometimes known as sensory processing disorder. This can include a heightened sensitivity (hypersensitivity) or reduced sensitivity (hyposensitivity) to sensory experiences. Sensory seeking refers to actively seeking out certain sensory experiences, such as craving deep pressure or being drawn to specific textures or sounds in order to regulate sensory input. On the other hand, for those with heightened sensitivity, everyday environments can quickly become overwhelming, and it can be all too easy to end up in a state of sensory overload.

Overload happens when the nervous system is bombarded with too much information all at once. The body interprets this as a threat, activating a protective mechanism designed to restore balance and prevent further distress. Sensory overload can manifest in many ways—sudden fatigue, difficulty concentrating, anxiety or irritability. Sometimes, it can be mistaken for emotional distress or even a panic attack.

Luckily, there are some helpful strategies for managing and preventing sensory overload. First and foremost, it’s important to remember that the goal is to accommodate sensory needs, not to ‘fix’ them.

Understanding Interoception in Autism: A Guide to Sensory and Emotional Self-Regulation

Interoception, often described as the body’s “sixth sense,” is our ability to notice and interpret internal signals. It plays a key role in helping us understand how we feel both physically and emotionally.

For many autistic adults, interoceptive processing works differently. Some may feel signals intensely, while others barely notice them until they’re overwhelming. For example, you might feel your heartbeat pounding so strongly that it’s hard for you to focus, or you might not realize you're hungry until you feel shaky or irritable.

These differences can make it harder to identify needs, regulate emotions or explain what’s happening in your body—but they’re a natural part of the autistic experience.

By building interoceptive awareness, autistic individuals can develop strategies to better recognize and respond to internal cues and improve well-being.

.webp)