Key Takeaways

- Pathological demand avoidance (PDA) is a behavioral profile often associated with autism, but is also seen in other groups, like those with ADHD.

- PDA is not considered a clinical diagnosis, but there is debate over its classification.

- Defining traits include an intense drive for autonomy, where demands, including everyday demands like sleeping and eating, may threaten a sense of control.

- Support strategies for PDA include managing and reducing demands where possible, and employing strategies to reduce overall anxiety and stress.

- Research on PDA is currently limited, but there are many advocates for increased focus on this trait.

Picture this: you come home from a long day at work, and become frozen by even the idea of cooking dinner, or cleaning up your home, or taking a shower. You know you have to be doing something, but even thinking about another task ratchets up your anxiety to the point you feel like you can’t function. If this sounds like something you’re dealing with, you aren’t alone: you might be experiencing demand avoidance.

Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) is a behavioral profile most often connected to autism, where demands trigger an intense need to resist or avoid. This can happen for different reasons: sometimes demands become genuinely overwhelming (like eating, sleeping, showering, or even turning off the lights), leading to freezing up or distress. But demands can trigger avoidance even when they're not overwhelming because they threaten autonomy or control.

While PDA isn't a formal diagnosis, it's recognized as part of a constellation of behaviors often associated with autism or other neurodevelopmental profiles like ADHD.

Other more affirming names for PDA have been suggested, such as Persistent Drive for Autonomy, Extreme Demand Avoidance (EDA), and Rational Demand Avoidance (RDA). However, for the purposes of this article, it will be referred to as Pathological Demand Avoidance, as this is the most common term in the US.

Read on to learn what PDA is, what it feels like, and why it’s often misunderstood.

What is Pathological demand avoidance (PDA)?

Pathological demand avoidance is a behavioral profile where external and internal demands can overwhelm an individual and cause severe anxiety. Those with PDA may determinedly avoid those demands, including things they might enjoy.

According to the PDA Society, pathological demand avoidance can be a dimensional trait, where individuals might appear sociable, but have trouble making deep friendships due to the demands placed upon them, use social strategies as a part of avoidance, and can suffer intense mood swings.

Kelly Whaling, Ph.D., Prosper psychologist, says, “PDA is a term describing a profile characterized by extreme, anxiety-driven avoidance of everyday demands and requests. This even applies to tasks that might seem minor or enjoyable to a person, like playing a video game they are looking forward to, which can be really confusing for the person experiencing it!”

Those with PDA often struggle with the ordinary demands of daily living, such as:

- Eating

- Sleeping

- Going to the bathroom

- Going to work or school

- Completing daily tasks

PDA has its origins in the 1980s, when developmental psychologist Elizabeth Newson, OBE, described children in her clinic as showing an “obsessional avoidance of the ordinary demands of everyday life.” While the first academic paper on PDA was published by Newsom’s team in 2003, it remains understudied, and critically so for adults.

It’s important to know that PDA is not a diagnosis, but a part of a profile or behavioral pattern of an individual who likely has autism, ADHD, or other neuropsychological differences. Clinicians may describe PDA as:

- Part of executive dysfunction, sensory issues, and anxiety

- Difficulty with communication, emotional, learning, and processing challenges

- Having intense social interaction patterns (preferring a few friends to many)

- Strongly preferring “safe” interests

- Displaying a heightened sensitivity to stress

- Preferring rigid routines that limit external and unpredictable demands.

Christal Castagnozzi, M.Psy., C.Psych, psychologist and clinical director at Thrive Psychology, says PDA is not the same as disliking doing a task or procrastinating.

“Regular stress is the body's natural reaction to pressure or demands. With stress, individuals will be able to carry out actions and participate. However, when we have a PDA profile, it makes task completion very unlikely. PDA is a stress response, but the intensity and severity are above what a typical ‘stress’ response would be,” she explains.

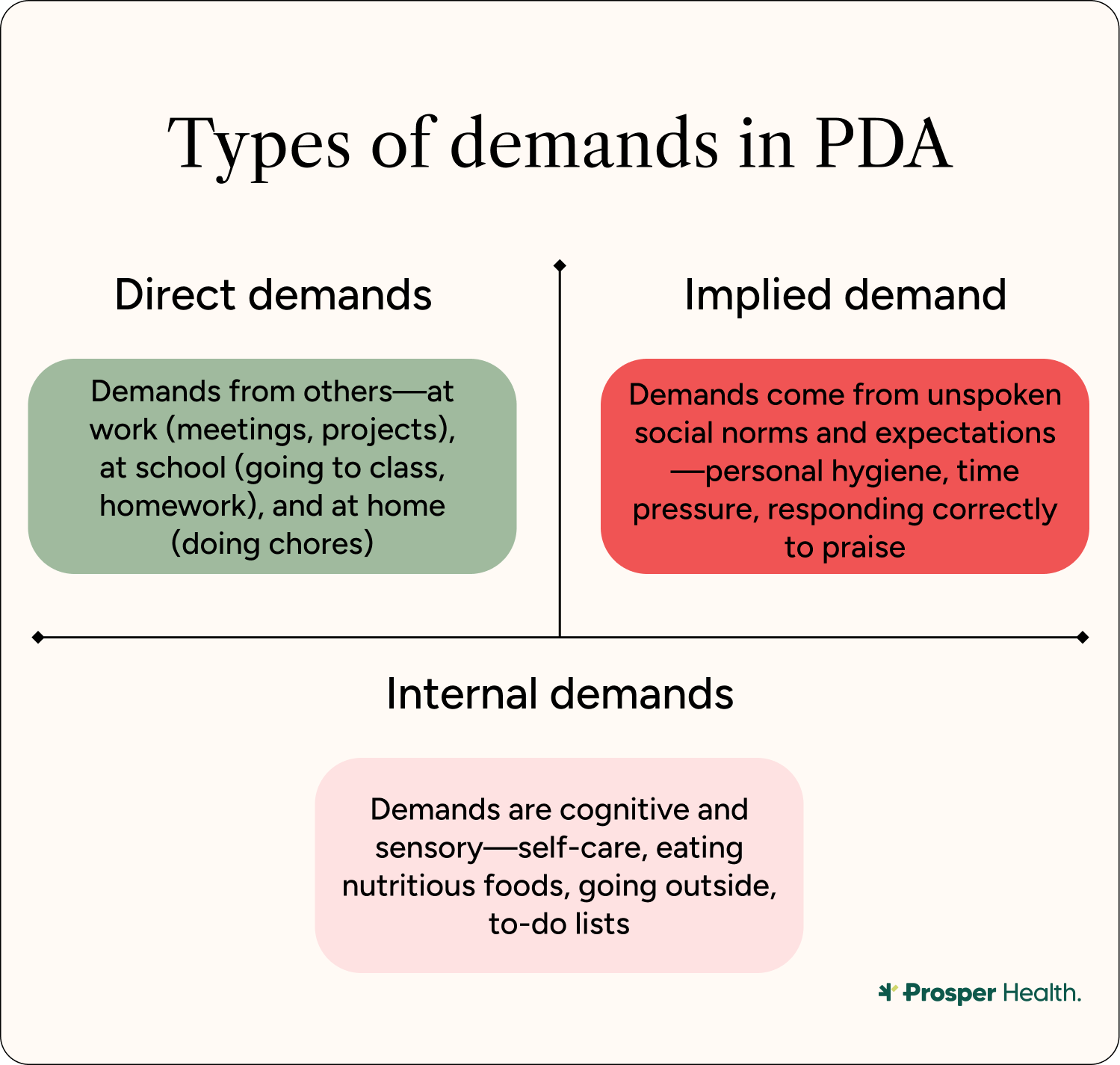

A demand, Dr. Castagnozzi says, can be anything that stresses an individual’s equilibrium. There are several kinds of demands to keep in mind.

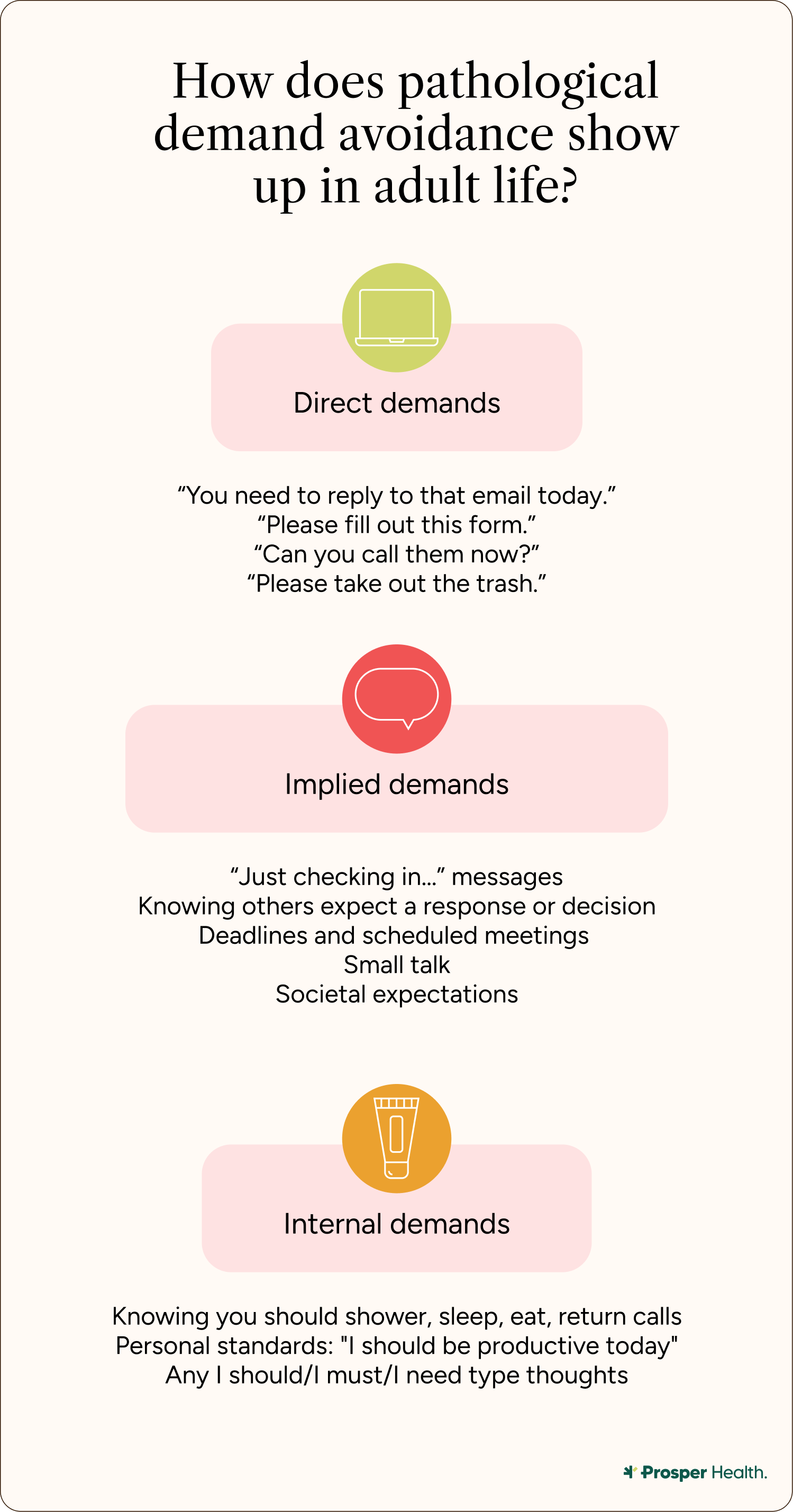

Direct Demands

Direct demands sound like what they are: demands that a person is asked directly to complete. Examples of this could be work projects, attending meetings, attending lectures, and completing classwork.

Indirect Demands

Indirect demands can be subtle or implied. Some examples can include societal norms and expectations, where pressure is implied rather than stated. Other indirect demands include the pressure to reply to messages or emails, as well as complete personal hygiene tasks.

Sensory input can also be an indirect demand, as sensory overload can create a space that feels inherently uncomfortable; for example, a loud room can demand too much attention and create physical challenges.

Similarly, cognitive demands are tasks that require sustained focus and attention or intense thought, are also indirect demands.

Perceived Demands

Like indirect demands, perceived demands are subtle, and often have to do with the pressure of expectation on an individual. For example, if someone with PDA is praised for doing a good job, there is a perceived demand that they perform the same task to the same level of completion the next time.

Self-Initiated Demands

Self-initiated demands originate with the person who has PDA, where even pleasurable activities like hobbies and self-care can feel like obligations rather than choices, resulting in inertia and inability to enjoy activities that were once fun or fulfilling.

How does PDA present in adults?

While limited research exists on how PDA presents in adults, practitioners are able to identify certain traits that show up across the board in those with PDA.

“PDA can present in relationships of all kinds in adulthood. Whether it be a romantic relationship, workplace interactions, or social interactions,” Dr. Castagnozzi says. It also shows up in behaviors like “doom-scrolling,” or in chronic avoidance, where individuals prefer to be alone or in safe spaces rather than seek out novel interactions.

While one small study suggests that up to 20% of autistic individuals may demonstrate some PDA traits, a relative minority of autistic people align with all characteristics of a PDA profile. More research is needed on the overlap of PDA and autism, especially in adults.

“An intolerance for uncertainty, or a need for routines/sameness, is a core diagnostic feature of autism. For autistic individuals, uncertainty about what might happen can feel threatening because the inability to predict or control outcomes activates threat responses. What appears as "avoidance" is actually a desperate attempt to maintain the predictability necessary for autistic self-regulation,” elaborates Dr. Whaling.

Crucially, autistic individuals aren’t the only ones who can experience PDA. PDA occurs in people with ADHD at a higher rate than in allistic individuals. A 2020 study suggests that PDA traits could actually be more common in those with ADHD than autism. PDA may also coincide with diagnoses

like complex PTSD (cPTSD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), though the relationships aren't entirely clear.

The PDA profile includes many traits other than an ongoing resistance to demands, and not everyone who experiences demand avoidance or self-identifies with PDA may exhibit all of these traits in the same way.

Some people may mask PDA traits, experiencing them internally. However, demands are cumulative, so while an individual may constantly be under stress, others may have no idea that they're experiencing an overload of demands until they freeze up or shut down. The following are examples of how PDA may show up in autistic individuals.

Desire for autonomy

At the core of PDA is the desire for autonomy. In fact, PDA advocates have pushed to redefine PDA as "persistent drive for autonomy” or “pervasive drive for autonomy” rather than pathologizing the trait.

This desire for autonomy and control is driven by extreme anxiety or panic brought on by demands. Being in control helps mitigate anxiety.

Heightened Emotion

Those with PDA can experience heightened emotions or mood swings when faced with demands, or shifting demands. Emotional changes are a direct result of threats to autonomy and control.

Other people may not understand these rapid mood changes, because those with PDA may mask their anxiety and emotions up to a certain point.

Impulsivity

While impulsivity is not as commonly associated with autism, those with PDA may be perceived as acting impulsively. However, impulsivity (or perhaps social behavior that feels unpredictable to allistic folks) may have to do with avoiding demands: the anxiety of a new demand, for example, can cause a fast change of behavior to avoid the new stressor.

Social behavior

Autistic individuals with PDA often exhibit great social dexterity, since they get practice effectively avoiding and resisting demands. Many people with PDA have strong social skills and can be charismatic in their avoidance of new demands. Those with PDA often have a social drive, but may be struggling internally with shame over their avoidances.

Intense fixations

Intense fixations have been described by some individuals with PDA. While special interests are common among autistic people, those who are both autistic and have PDA describe intense fixations on other people—either known, famous, or fictional—which may differ from other autistic folks without PDA.

Daydreaming and fantasy

Some people with PDA profiles have described feel comfortable with roleplay and fantasy; daydreaming can provide escape from demands and stress. However, these daydreams may be repetitive, suggesting a level of rigidity within a set of limits.

Creativity and humor

When Newsom first described PDA, she noted that those who exhibited the trait used novelty, humor, and flexibility as strategies to avoid demands. Those who also have PDA may use creativity much in the same way they use daydreaming: to escape the relentless pressure of demands. It is unclear as yet how this trait relates to autism.

Responsiveness to support strategies

Those with PDA don’t always respond to traditional social and/or support approaches, like praise or strict boundaries. People with PDA may shy away from praise because of the implicit demand it places on completing the same task the same way the next time, for example.

Additionally, people with PDA may struggle when their options are limited, because it reduces their autonomy. This differs markedly from autistic individuals without PDA, who may prefer limiting the number of decisions they need to make while in a state of overwhelm. Those with PDA, however need to have as much autonomy as possible.

Strategies to avoid demands

PDA individuals may employ a number of approaches to avoid demands, including social strategies. These include:

- Making excuses to get out of a task

- Deflection and distraction (changing the subject, creating a diversion, being charming, flattering)

- Negotiation and bargaining

- Procrastination on a task they agreed to complete

- Leaving the situation or person imposing a demand

- Retreating into fantasy or role play

When these strategies fail, those with PDA may become distressed or overwhelmed. This response, which may include anger or a meltdown, and can lead to shutdown, is not a voluntary reaction.

“Understand and approach the situations with compassion and curiosity rather than judgment. PDA can be perceived very negatively and can be seen as ‘oppositional,’ but it is a true stress response and comes from a place of overwhelm or fear rather than ill intent,” says Dr. Castagnozzi.

Remember, demands are cumulative, and those with PDA and autism may be masking their overwhelm until they reach a breaking point.

What does PDA feel like?

Overwhelm and panic are two likely outcomes of too many demands, or even a single distressing demand, and can ultimately lead to shutdown if improperly managed.

Dr. Castagnozzi says that PDA can be absolutely debilitating.

“It feels like an absolute spiral! If someone tells me to do something or their tone indicates that I have to do something, it sends me into a standstill and creates a roadblock that I can struggle to overcome,” she adds.

Dr. Castagnozzi says if someone is already on their way to completing a task and is given another one—or is yet again reminded to do the task they’re already on the way to complete—they may or may not continue to the task. That’s because tasks are already overwhelming, and if the individual is presented with more demands, they’ll shut down entirely.

Speaking from experience, if I am juggling half a dozen tasks and get a text message, I can enter into a frozen state where I can’t complete anything else—even if I want to complete all the items on my checklist. I also find it difficult to shift from one task to another. As a result, I may end up avoiding messages for days, or enter a state of full burnout.

I liken it to having a full glass of water in my brain: if my glass is already near full and another is poured into it, the glass spills over but doesn’t empty entirely. That’s what living with PDA feels like: your glass is never empty enough, and you’ll always be spilling something over the side.

“Many adults describe profound isolation, rarely leaving the house, scared and ashamed of what's wrong with them, exhausted by a nervous system that systematically steals access to meaning and connection. People have described it as a hopeless lack of control over their own reactions or life,” Dr. Whaling adds.

Why is PDA so controversial?

PDA is an understudied set of traits that some clinicians believe don't actually indicate a new, holistic pathology. Therefore, the label can be controversial. Research on PDA, especially in autistic adults, is extremely limited. The label “PDA” as pathologizing has been critiqued, as well—while other researchers argue it’s an important label.

The label is pathologizing

Many PDA advocates insist that naming the traits a “pathological” demand avoidance is demeaning and a misnomer. Rather than critiquing the systems that pressure autistic individuals and PDA to act a certain way, it upholds social and medical hierarchies.

“The term itself can be controversial, and [some] PDA-ers prefer the term "Persistent Drive for Autonomy" as it's more neuro-affirming and trauma-informed,” Dr. Castagnozzi confirms.

Research is limited

PDA is not well-understood, especially in adult populations. Originally developed by a child psychologist, PDA may not be suitable as a descriptive trait for adults, and more research is needed.

Dr. Whaling says that some scientists “argue that PDA has not been empirically validated as a distinct syndrome and fails to meet established criteria for diagnostic validity. As a field, we also cannot agree on whether it is transdiagnostic across multiple conditions, or, unique to autism.”

There's a lack of nuance

Autism is a dimensional disorder, and PDA may take focus away from more specific and established elements of autism that are useful for understanding a person's presentation. Additionally, PDA may mask environmental or social conditions that influence someone’s inability or aversion to completing tasks. PDA is also not a diagnosis, and so can be applied flippantly.

Support for the PDA label

Despite criticisms, many hold that the PDA label is helpful and offers value to our understanding of neurodiversity—and ensures future research.

Increased understanding and community building

Some advocates of PDA argue that labels help increase understanding—contextualizing lived experiences that may otherwise fall outside of the “typical” autism traits. Having the PDA label allows these individuals to find support and community where otherwise there may be none.

Access to support

Putting a name like PDA to experiences also helps in a clinical setting, allowing individuals to access support where otherwise they might be dismissed. Understanding PDA traits can help individuals refine what accommodations may help them at work or school.

Cultural awareness

Advocates argue the PDA label increases awareness and understanding across media and in everyday situations. The more often allistic folks learn about PDA, the better they may understand how to support their loved ones. With more research, more opportunities for understanding can be revealed, and further, more acceptance for adult autistic individuals with PDA.

Support strategies to help with PDA

Several strategies can be helpful in managing adult PDA. All strategies should be anchored in respect and understanding. Dr. Whaling says that symptoms of PDA can decrease as someone ages—which suggests coping strategies can help.

“Ultimately, the goal of trying to cope with demand avoidance isn't to make yourself ‘obey better’ but to expand your window of tolerance for demands by reducing your baseline anxiety and developing skills that increase your coping capacity,” Dr. Whaling adds.

Here are some examples from Dr. Castagnozzi and Dr. Whaling:

For those with PDA

It's important to make sure that your anxiety is well addressed via therapy, medication management, and stress reduction.

"The natural response to threat and anxiety are the primary drivers of demand avoidance behaviors, which means interventions must address the underlying anxiety rather than attempting to modify behavior through consequences. If you can address the anxiety, the avoidance often becomes more manageable," Dr. Whaling says.

Once you have taken steps to ameliorate anxiety, there are other kinds of support as well.

Nervous system regulation

Take breaks, quiet time, and engage in sensory friendly stim toys. Weighted blankets can also help.

“Once you feel the spiral, take a step back and take a pause and come back to it within your own time frame when you feel ready. This helps take the pressure off and allows for a reset,” says Dr. Castagnozzi.

Create a psychological escape

Engage in positive affirmation and self talk to escape thought spirals. Dr. Castagnozzi suggests reminding yourself, “I don’t have to do this,” “I can put this down,” and “I can take a break,” for example. It may even be helpful to create physical reminders of these mantras.

“Build in demand-free recovery time where nothing is expected of you. You might find it helps to have information about what to expect, though you also need the flexibility to change plans when your capacity shifts,” Dr. Whaling adds.

Change your physical state

To escape a difficult reaction, splashing your face with cold water, screaming into a pillow, or jumping up and down can externalize the internal reaction and make it easier to deal with.

Figure out necessary tasks

Some tasks are more important, while others are relatively optional. For example, cleaning the dishes may be more necessary than vacuuming the rug.

“Look at all the things you're "supposed" to do and figure out which ones are actually necessary versus which ones are just preferences or conventions that don't really matter,” Dr. Whaling says.

Seek accommodations

If you experience PDA, inform others of your day-to-day needs when it feels safe to do so. Be flexible in your approach and give yourself grace when engaging in work or school, and explore different ways to approach them to reduce demands.

One thing that may be helpful is a visual schedule, which may be perceived as less rigid and demanding than a list, Dr. Whaling suggests.

Consider therapy

PDA and any pursuant anxiety can be improved with therapy, Dr. Whaling says. “You might benefit from therapy approaches that target your intolerance of uncertainty, and physiological responses to threat/distress tolerance,” she explains.

While therapy practices like CBT or DBT might need modification, somatic strategies that focus on bodily response can help deal with some of the physical side effects of PDA, like racing heartbeat or jitteriness. Prosper Health offers neurodivergent affirming therapy that can help you manage the impact of PDA on your life.

For family, caregivers, or loved ones

Indirect language usage

Direct language can feel like a demand, so use indirect language when framing requests. Dr. Castagnozzi suggests leaving things open-ended. Instead of saying “Can you do this now?” or “You need to…,” phrases like “I wonder if…” or “Maybe we could explore…” can leave the door open for those with PDA to make their own choices. However, it is important to note that some autistic people may struggle to interpret this language; it’s best to discuss changes to language usage ahead of time to know if it works for everyone.

Provide choices

Instead of making a direct demand, present a list of choices. However, “they must be real choices, and the person must be given the autonomy to choose and not forced into a specific choice,” says Dr. Castagnozzi.

Be adaptable

Be flexible with your expectations: not every demand made will be met, and accepting “no” as a complete answer is important. Be open to negotiation, and choose your battles.

“Having understanding and curiosity gives us the space to pick and choose our battles so we aren't sending our loved one for a spiral over something that may be a big deal for them but a minor inconvenience for us,” Dr. Castagnozzi confirms.

The bottom line

PDA is a complex set of traits that some autistic individuals, even adults, can exhibit. If we give those with PDA autonomy and choice, we can prevent shutdown and overwhelm. More research needed to better understand PDA, but in the meantime, we can employ strategies to help manage PDA effectively and help those with it feel seen and understood.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

What is the root cause of pathological demand avoidance? PDA is not well-researched, but autistic people and those with ADHD are more likely to have PDA. Demand avoidance occurs when those with PDA feel as though their autonomy is being limited.

How is pathological demand avoidance diagnosed? PDA is not a diagnosis, but clinicians can assess whether you have PDA traits such as a heightened sensitivity to stress, difficulty with demands, and intense relationships.

How does pathological demand avoidance affect daily life? PDA can make it difficult to do daily tasks like cleaning the house, taking out the trash, responding to text messages or emails, showering, and eating. Anything that can be perceived as a demand on autonomy may be affected.

Sources

https://adc.bmj.com/content/88/7/595.short

https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/what-is-pda/

https://www.pdasociety.org.uk/research-professional-practice/origins-of-term-pda/

https://pdanorthamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Identifying-PDA-in-Adults-Dr-Huffman.pdf

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6373319/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00787-014-0647-3

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0891422220301633

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4820467/

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/education/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1179015/full#B51

Related Posts

Meltdowns in Autistic Adults: Why They Happen, What They’re Like, and How to Live with Them

When many people hear the word “meltdown,” they might envision a kicking-and-screaming child, lashing out because their parent or caregiver said “no.”

While that is an accurate description of a typical child meltdown, a meltdown in an autistic adult is entirely different, and not to be confused. In fact, in many cases, meltdowns in autistic adults can look like the antithesis of a childhood tantrum. Instead of engaging in "why won't you give me what I want!?" goal-oriented behaviors that are synonymous with tantrums, autistic adults usually need to get away from people and into a calm, dark, safe space during a meltdown.

The most important thing to remember about an autistic meltdown is that it’s not a choice, but an involuntary nervous-system response to intense overload or stress. If someone is experiencing a meltdown, they are not intentionally acting out: They are dealing with complex emotions just like the rest of us, and don’t deserve the ongoing stigma that is attached to autism—and by extension, meltdowns.

Victoria Mindiola (they/theirs/she) is an autistic person who works as an inclusion consultant and educator, focusing on advocacy for neurodivergent students. When Mindiola experiences an autistic meltdown, they say they frantically need “to find a place that is safe and dark and quiet and empty of people.”

Unfortunately, the stigma around autism and meltdowns remains because adult-focused research and resources are still lacking. While there’s plenty of research available on autistic meltdowns in children, there is limited data from the perspective of autistic adults.

In this article, we’ll provide a comprehensive breakdown of autistic meltdowns in adults: What they are, why they happen, how to identify early signs, and how to support yourself or someone else.

Sensory Overload in Autistic Adults: Why It Happens and How to Cope

For autistic and neurodivergent adults, sensory overload can feel like it hits all at once. Imagine you’re in a crowded restaurant. At first, the talking all around you becomes intrusive, and you can’t concentrate on the person across from you, no matter how hard you try. Then, the repeated sound of clinking of glasses and forks on porcelain intensifies, grating at your nerves, and the smell of perfume on the woman next to you becomes unbearably strong.

Suddenly, you’re in full-body panic mode because this combination of sensory experiences is simply too much. Allistic people can compartmentalize and block out these types of input, but autistic people often cannot.

Sensory processing differences—formerly referred to as a “sensory processing disorder”—are the variations in how the brain receives, interprets, and responds to information gained through your senses from the environment and the body. Autistic people’s sensitivity to stimuli will vary depending on the individual.

Sensory overload, on the other hand, can happen when a neurodivergent person’s brain becomes so overwhelmed by sensory information in an environment (think: sights, sounds, smells, textures) that their body goes into a state of panic and fight or flight mode.

“Sensory overload, or strong sensory input, can often be described as ‘physically painful’ or ‘making my skin crawl’ by autistic adults,” says Jackie Shinall, PsyD, head of reliability and quality assurance at Prosper Health. “For example, they don’t necessarily feel anxious or stressed by the input, but rather uncomfortable overall, especially physically.”

While anyone can experience sensory issues and sensory overload, they are especially common among autistic adults and neurodivergent people more broadly. In fact, a 2021 study published in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders surveyed autistic adults and found that 93.9% reported being extra sensitive to sensory experiences. Autism and sensory overload often go hand-in-hand.

If you have questions about sensory overload in autistic adults, you’ve come to the right place. In this article, we'll cover what sensory overload is, why it happens, what it feels like, and how to prevent and recover from it.

.png)

What Is Stimming? A Guide to Autistic Self-Regulation and Expression

Self-stimulatory behavior, or "stimming", is a physical behavior used by autistic and other individuals (including those who are allistic) to regulate emotional or sensory stress, sensory seek, and/or express their emotions. In autistic people, stimming is often repetitive and is a way to calm their minds and bodies.

Personally, I have stimmed my entire life in many ways. Notably, I am always carrying a rolling stim toy with me. It helps to ground me when I get anxious, or when the noises in a room are too loud or overwhelming.

Everyone stims, whether they realize it or not. If you’ve ever bounced your knee while bored, or clicked a pen open and closed, you’ve stimmed. But for autistic folks, stimming serves a key role in sensory and emotional management. It’s not something to fix, but rather something to understand.

In this article, we’ll explain what stimming is, why it happens, and how to support yourself or someone around you who stims.

.webp)